What is being done about the gender cum laude gap among PhDs?

More than a year has passed since Dutch universities were confronted with a long-overlooked disadvantage for women trying to climb the academic ladder. Female PhD candidates, it turned out, are far less likely than their male counterparts to earn a cum laude doctoral degree. What actions has Tilburg University taken to make its honors system for PhDs more equal?

In the academic world, gender inequality runs deep. Studies have only just begun to plumb the depths of the gender gap that persists in science, showing that women face discrimination in hiring, salary, promotion, citations, authorship credit, letters of recommendation and invitations to give talks.

In October last year, the Dutch daily newspaper NRC Handelsblad added another gender-related obstacle to that list. In an article captioned ‘Half of all PhDs are women, but they rarely receive cum laude’, the newspaper showed that male PhD candidates across all Dutch universities are systematically favored when it comes to being granted the prestigious Latin honor.

The chances of earning a cum laude distinction was found to be 1.5 to 2 times higher for male PhD candidates at 50 percent of universities. At several universities, an even wider gender gap was observed.

Tilburg University

Although not as pronounced as at some other universities, the gender cum laude gap among PhD candidates also exists at Tilburg University. The figures published in NRC showed that a cum laude distinction was awarded to 6.4 percent of men who obtained a PhD degree from Tilburg University between 2009 and 2017, compared to 5.7 percent of women.

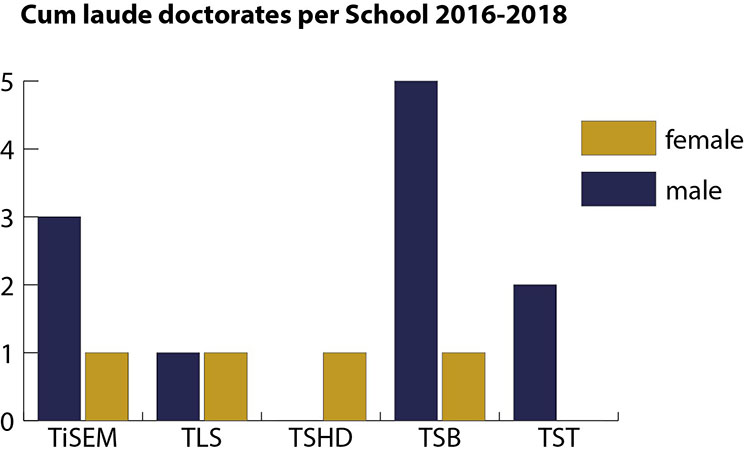

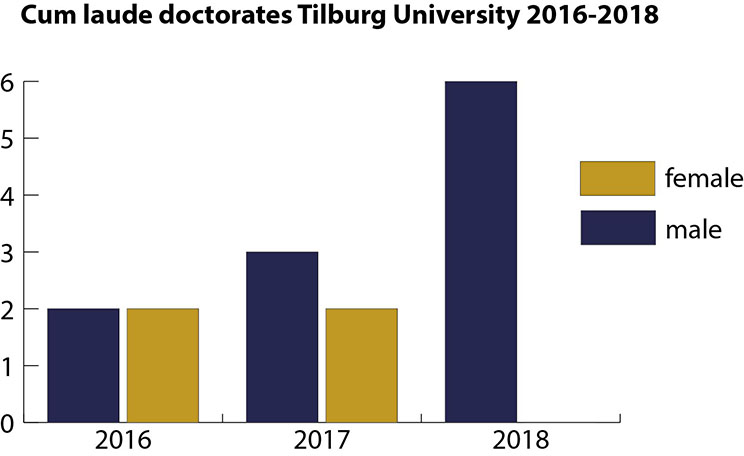

NRC did not include 2018 in its calculation, since the year was yet to come to a close when the article was published. Figures recently requested by Univers show that starker gender differences arise when the year 2018 is taken into account. In that year, six out of all six cum laude PhD honorees at Tilburg University were men. Over a three-year period spanning 2016-2018, as the graph below shows, a cum laude distinction was awarded to a total of fifteen doctoral candidates at Tilburg University—eleven men and four women.

In three cases, a cum laude distinction was proposed but not granted, because the PhD committee voted against it. Among the three rejections were two female candidates, amounting to 67 percent. Although these numbers are obviously too small to draw any conclusions, they do fit with the suggestion that female PhD candidates are evaluated less favorably than men—they receive less cum laude distinctions, and more rejections.The cum laude differences between male and female PhDs seemed to come as a surprise to the Dutch academic community. Tilburg University spokesperson Tineke Bennema stated that the university had no knowledge of the gender differences in cum laude doctorate degrees prior to the NRC publication. Similar statements came from other universities.

Shocked

Tilburg Law School doctoral candidate Anne de Vries, who served as the president of the PhD Network Netherlands (PNN) when the article broke last year, said the news shocked her. “At PNN, we were not aware of this gender inequality.”

“It is deeply worrying,” she added. “In a scientific environment, you would hope that people are capable of judging you by the quality of your work. But this has made it painfully clear that gender remains a factor in how your work is perceived, from the earliest stages of your academic career.”

Women make up nearly half of all PhD graduates

Men and women earn PhD degrees in roughly equal numbers in the Netherlands, with a slight majority of male PhDs. The proportion of female PhD graduates climbed from 8.8 percent in 1985 to nearly 50 percent in 2015, slightly decreasing again in the years 2016-2018.

Tilburg University has a similar gender distribution. The university’s doctorate board provided Univers with an overview of PhD degrees handed out over the past few years. This overview shows that women constituted 50 percent of PhD recipients in 2016, 48 percent in 2017, and 45 percent in 2018. Taken together, female candidates made up nearly 48 percent of Tilburg University’s doctorate recipients from 2016 until 2018. In the current year, 48 percent of PhD graduates were women.

False start

The cum laude predicate is an acknowledgment of outstanding academic achievement, which is rarely given to PhD candidates. From 2016 until 2018, a total of 378 doctoral candidates successfully defended their PhD thesis at Tilburg University. Since a cum laude was awarded to fifteen of them, the “excellent few” made up a mere 4 percent of all doctorate recipients.

“We cannot let gender bias determine who gets to be considered excellent”

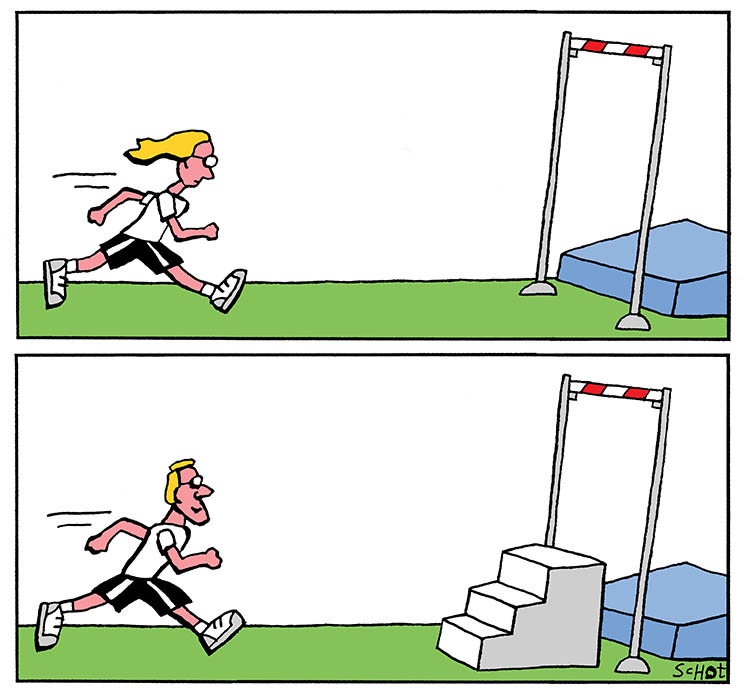

That is precisely why it’s so alarming that women are systematically less likely to be granted the prestigious academic honor, De Vries says. “Cum laude is an exceptional recognition of excellence. Receiving such recognition can be career-making for young scientists, especially considering how difficult it is already to continue in academia after completing a PhD,” she explains. “We cannot allow gender bias to determine who gets to be considered excellent, because that gives women a false start of their academic careers.”

Gender bias

According to De Vries, gender bias is the only explanation for the fact that men are more likely to receive a cum laude distinction for their dissertation. “In my field of expertise, I even get the impression that female students graduate cum laude more often than male students. If women perform equally well or maybe even better during their masters, why would they suddenly be outperformed by men when they move on to a PhD?”

The answer, according to De Vries, is that the cum laude regulations for students are more objective than the honors system for doctoral candidates. “Female PhD candidates do not lack excellence. What they lack is an objective evaluation system that eliminates implicit biases as much as possible.”

Students versus PhDs

The observation made by Anne de Vries—that female students are awarded a cum laude university degree more often than male students—is supported by figures from other universities. For example, figures shared with Nijmegen’s independent university newspaper Vox revealed that female Radboud University students consistently graduate cum laude more often than male students.

“Female PhD candidates do not lack excellence. They lack an objective evaluation system”

This may also be true for Tilburg University students. While the exam committees of most Tilburg University faculties were unable to provide numbers about the gender balance of cum laude graduates, the Tilburg School of Social and Behavioral Sciences did produce such an overview at the request of Univers.

These numbers show that 20 percent of female master’s students graduated cum laude from the Tilburg School of Social and Behavioral Sciences between 2016 and 2018, compared to only 12 percent of male students.

Closing the gap

Anne de Vries is clear about it: the gender cum laude gap must close. But how? At Tilburg University, discussions on that question have taken place ever since the gap was revealed.

Anna Berti Suman, a PhD candidate at Tilburg Law School and a former representative on the University Council, took part in those discussions. “I believe everyone within the university—from the board of executives to the PhD community on campus—agreed that the honors system for PhD candidates must become more equal. But because gender bias is such a complex and pervasive problem, agreeing on how to tackle it proved to be a lot more difficult.”

“A gender quota would not deal with the root of the problem”

One of the suggestions made by the executive board was to establish a quota system, as a way of guaranteeing that cum laude is awarded to an equal number of male and female PhD candidates. This idea received little support from the members of the University Council. Anna Berti Suman, too, spoke out against a quota system. “I don’t think mandated quotas are the answer. They could undermine the value of cum laude and, more importantly, they don’t deal with the root of the problem.”

New measures to beat bias

If quotas are not the way to go, how will Tilburg University beat biases that influence cum laude decisions made by PhD committees?

To take gender bias out of the honors system, the university has made changes to its PhD regulations. The new regulations, which came into force on 1 December, impose stricter requirements on the composition of PhD committees. This should increase diversity and prevent all-male doctoral committees. In addition, the university will initiate an anti-bias training program to promote equal opportunity and equity.

More women on PhD committees

Under the new regulations, each PhD committee must include at least one woman. That means all-male PhD committees now belong to the past, but overwhelmingly male committees may still occur.

Anna Berti Suman believes the importance of gender diversity on PhD committees should not be overlooked. “Rather than slightly more diverse committees, I hope we will be able to achieve true and rich diversity,” she says. “It’s important to have balanced PhD committees, not just gender-wise but also in terms of cultural backgrounds, because this brings different perspectives, experiences and approaches.”

And there is another, less obvious reason for wanting an equal number of men and women on PhD committees. Studies have found that male professors tend to evaluate men more favorably than they do women, possibly because they recognize themselves in young male academics. Such unconscious biases are more likely to occur when PhD committees lack diversity.

Smaller pool

At Tilburg University, female professors are currently still vastly underrepresented on PhD committees. Over the past three years, more than 80 percent of committee members were male.

An interesting observation is that last year, when a whopping 100 percent of cum laude recipients were men, the proportion of male committee members was also exceptionally high—92 percent.

A much-heard reason for the lack of women on PhD committees is that full professors and other high-ranking academics—who, as authorities in their field, are allowed to sit on PhD committees—are often men. The pool of top female academics, in other words, is too small to achieve gender balance on PhD committees.

This argument does not hold, Berti Suman says. “Yes, we need more female professors. But we can’t wait for that to happen. To me, it’s impossible to believe that women can’t make up half of a PhD committee because there aren’t enough female academics with a particular expertise,” she explains. “If we don’t have enough female professors and associate professors at our own university, qualified women from outside Tilburg University should be appointed as PhD committee members.”

Not either-or, but both-and

Anne de Vries points out that having more female professors on PhD committees is important, but not enough to fix the problem.

“Women, too, can be biased against women,” she says. Therefore, she believes offering anti-bias trainings to all professors and senior academics who may sit on a PhD committee—men and women—is a good idea.

“The actions taken by the university are a start, but definitely not the end”

Still, she believes the new measures will not solve all problems. “It’s a start, but definitely not the end. Gender bias at universities is a stubborn problem without a quick solution,” she says. “For example, recent research on job applications in academia showed that the requirement to have one woman in each selection committee has not stopped biases against women.”

Because gender bias is so deeply ingrained in the academic culture, Anne de Vries says, it would be naïve to think that a few alterations to the PhD regulations can fix biases against female candidates. More measures, and more different kinds of measures, will be needed. “To confront this issue, we have to think in terms of both-and, not either-or.”

Clear requirements for cum laude

Beyond more balanced PhD committees and gender bias trainings, De Vries has a few more ‘ands’ to add. “Most importantly, the cum laude conditions for PhDs must be clarified. If there are objective criteria in place for deciding whether or not a dissertation should be rewarded with a cum laude, there is less room for prejudice,” she says. “Such objective criteria exist for the evaluation of bachelor’s and master’s theses, so why not for dissertations?”

Although Berti Suman endorses the university’s attempts to bring more structure to its cum laude procedures for PhDs, she worries that imposing stricter regulations may not pave the way for a fair and equal honors system. “I think the criteria that are currently being imposed have the tendency of over-regulating, making it extremely difficult to get a cum laude regardless of the candidate’s gender.”

“Too many rules and regulations could be counterproductive”

“While it’s good to enact stricter rules on the composition of committees, for example, I am worried that too many rules may increase the ‘bureaucratic burden’ to a point that we miss the real lodestar,” she explains, “which is more quality and integrity on PhD trajectories and assessments.”

Second opinion

There are possible measures against bias in cum laude procedures that do not involve stricter rules and regulations, Berti Suman says. Blind assessment, for example: “Blind assessment would ensure that a dissertation is judged solely by its quality, not by the sex of its author.”

Although it would seem impossible to keep a candidate anonymous to a supervisory committee at his or her own institution, an external committee could provide a ‘second opinion’ of sorts. “Perhaps we could have dissertations re-assessed by an independent committee that has no knowledge of the candidate’s gender.”

Berti Suman is hopeful that exploring measures like these, which don’t give rise to a tightening web of rules, will move Tilburg University towards the goal of ensuring the quality and integrity of PhD trajectories. But for now, Berti Suman is focused on bringing her own trajectory to a successful conclusion. “I am now myself very close to my own PhD defense,” she says, “and I am happy to say that I have a nicely gender-balanced committee.”

A changed mentality

After three years of PhD representation in Tilburg and on the national level, Anne de Vries has also turned her full attention to completing her dissertation. “I’m confident that PNN will stay on top of this, though,” she says. “During my time as president, I created a position for a PNN board member focusing specifically on diversity issues. The new president is also very involved.”

“However, it cannot come from the PhD community alone,” De Vries adds. “It’s important that the mentality among associate and full professors, mostly males, changes.”