Banned Books in the University Library

Reading whatever you want: it seems so obvious. But free access to knowledge and stories has not always been, and is not everywhere in the world, so self-evident. During Banned Books Week, libraries celebrate freedom of expression and highlight books that at some point have been banned, censored, or criticized somewhere in the world.

Banned Books Week (20–28 September) is inspired by the American Banned Books Week and is being organized in the Netherlands for the first time this year. Libraries across the country are participating. In the display case opposite the library desk, a selection of books that were once banned is exhibited.

Depending on the ideological climate

Banned books are of all times. For centuries, the Roman Catholic Church prohibited books that conflicted with church doctrine. In 2025, however, thousands of books are being removed from (school) libraries in the United States every year. In the eyes of political authorities they are “woke,” or their contents are seen as intolerable by conservative organizations.

Depending on the prevailing ideological wind, books may or may not be tolerated—meaning that they are either available or withheld from potential readers. In some cases, banned books were actively suppressed, and publishing, selling, or even owning them could be punishable by law, with all the consequences that entailed, depending on the country or historical period.

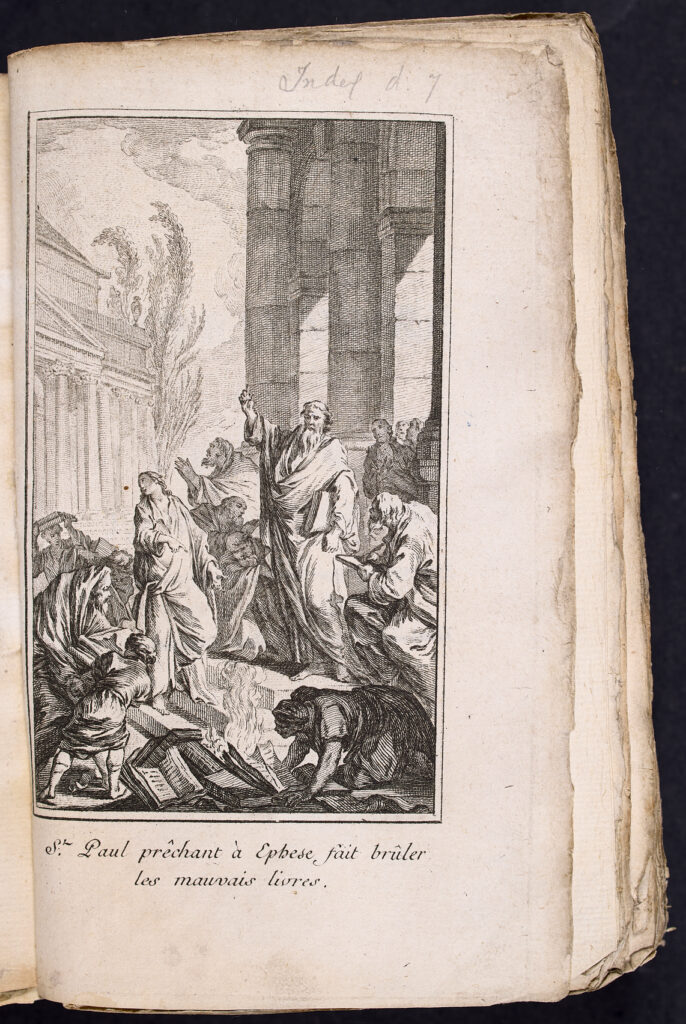

In other instances, church or state authorities issued strong condemnations, declaring that certain published works were unacceptable and that reading them was “corrupting.” In the most extreme cases, books were systematically burned. The Nazis did so whenever an author or a book’s content did not fit into National Socialist ideology or was despised as a form of culture.

Political, religious, sexual, or social grounds

Looking back at the history of banned books, the titles in question can roughly be divided into four categories: books condemned on political, religious, sexual, or social grounds. Both fiction and non-fiction could fall under scrutiny.

A 1618 publication about Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, for instance, was considered libelous and offensive. A reward of 500 guilders was offered for information leading to the printer or the author, whose name was not mentioned in the book. It was most likely François van Aerssen, also responsible for Gulden Legende van den Nieuwen St. Jan, which the States of Holland likewise denounced as a libel against Van Oldenbarnevelt.

Poet Joost van den Vondel was fined after addressing the conflict between Prince Maurice and Van Oldenbarnevelt in his tragedy Palamedes. During the French occupation, books were also banned or required alteration by order of the authorities. J.F. Helmers’ poem De Hollandsche Natie is a good example.

The Index of Prohibited Books

In the sixteenth century, the Roman Catholic Church established the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, or simply the Index: a list of banned books. From 1559 onwards the pope took charge, though theologians at the University of Leuven had already done much preparatory work. Books on the Leuven Index were not to be read, beginning with those of Luther.

Even Erasmus’ Praise of Folly did not meet with universal approval. In the early years of print, it was common practice for manuscripts to be submitted for church approval before publication, with the official permission (Imprimatur) printed in the book itself.

J.J. Scheuchzer’s Physica Sacra (15 volumes, 1735–1738) dealt extensively with the natural sciences in relation to the Bible. Its attempt to explain biblical events scientifically through physics was reason enough for authorities to strongly discourage reading the work.

Sexuality

Books were often banned on sexual grounds, especially in literature. Many novels or poems that contained (homo)sexuality or explicit love scenes were condemned, such as Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita and Hugo Claus’ De Metsiers.

Catholic moral teaching played a decisive role in these judgments. From 1937 to 1970, the Informatiedienst Inzake Literatuur (IDIL, Information Service on Literature) issued moral ratings for an average of 1,500 books each year.

Category I stood for “Forbidden reading,” II for “Seriously restricted reading.” Innocent children’s books received a VI. These ratings were distributed in biweekly bulletins to libraries, publishers, and subscribers throughout the book world.

Less offensive

If a book was deemed offensive or insulting to a certain group, it could also be banned—or at least altered. The first German translation of Anne Frank’s Diary was edited so that its contents would be less offensive to German readers.

In 1869, a letter to the editor in the provincial newspaper De Noordbrabanter criticized part of the book collection of the Provincial Society of Arts and Sciences (predecessor of the Brabant Collection).

Books stemming from the Enlightenment, in particular, were said not to belong in the reading room. The Society also censored medical books, removing some from the collection because of their illustrations—for example in the Verzameling van tegennatuurlyke gevallen en waarneemingen in de vroedkunde (Collection of unnatural cases and observations in obstetrics).