Do you let voting tools decide your vote? ‘Keep thinking for yourself’

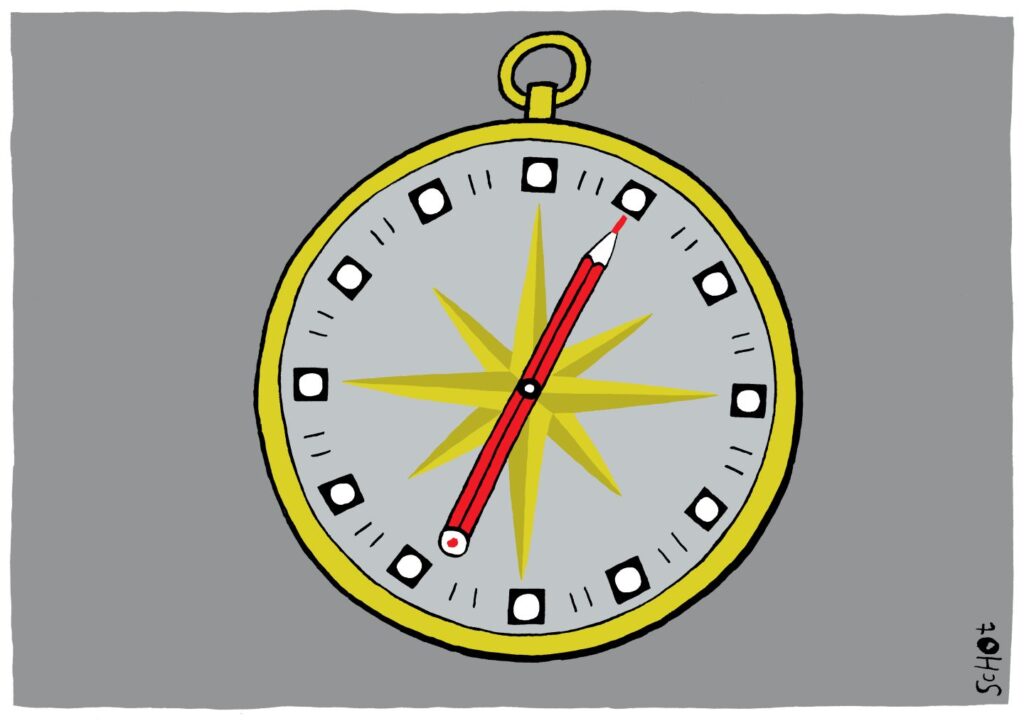

We’ll soon be heading to the polls again. But voting can be quite a task. Which of the 27 political parties will you choose – and why? Voting tools like Stemwijzer or Kieskompas help many people decide. But can we really trust them?

27 parties are participating in the upcoming national elections. That means there are just as many party manifestos to read — quite a task, and not one everyone looks forward to. That’s why voting tools are so popular. Through a series of statements, they show which party best matches your views.

During the 2023 parliamentary elections, Stemwijzer alone was completed over 9.1 million times. But what if people misunderstand how voting tools work and simply follow their outcome? They might end up voting for a party that doesn’t actually fit them. Naomi Kamoen from the Tilburg School of Humanities and Digital Sciences (TSHD) researches voting tools. What does she advise?

What do the Dutch actually use voting tools for?

‘Research shows that there are three types of voting tool users: checkers, seekers, and doubters. Checkers look to see if the outcome matches what they already had in mind. Seekers are looking for information, while doubters also want information but have little interest in politics — they sometimes even skip voting altogether.’

Do we know how many people base their vote on online voting tools?

‘Not exactly, that’s quite difficult to measure. It would be ethically irresponsible to prevent a certain group of people — the control group in an experiment, for example — from using a voting tool. We don’t want that.

‘We do know that the more information you have about parties and politics, the more likely you are to vote. Voting tools make it relatively easy to find information, so in that sense they have a positive effect on voter turnout. We also know that if the voting tool recommends a party someone was already considering, the likelihood of voting for that party increases.’

Who creates these voting tools? Are they independent?

‘In the Netherlands there’s a commercial market for voting tools. ProDemos, the maker of Stemwijzer, does receive subsidies for other projects, but those are not specifically intended for developing the tool itself.

‘They compete with Kieskompas, for example, for assignments — especially in local elections. Municipalities may say: “We want to have a voting tool made,” and voting tool companies can bid for that. Larger cities sometimes even choose to offer more than one voting tool.

‘In other countries it works differently. In Switzerland, for instance, there is one subsidized organization that offers the official voting tool.’

Can we assume that voting tools are reliable?

‘The government obviously wants citizens to have access to reliable election information, and with the large, well-known voting tools that’s usually the case. They test extensively, try out multiple phrasings, and examine how people respond.

‘But politics is complex, and if you want to highlight differences between parties through statements, you inevitably have to make choices.’

What role does framing play in voting tools?

‘Language is never neutral. If you say “something should not be prohibited” or “something should be allowed,” you’re essentially saying the same thing, because logically “not prohibiting” means “allowing.” Yet one of my studies shows that word choice matters.

‘People are more inclined to answer “no” or “disagree” to negatively framed questions (for example, about banning something) than to answer “yes” or “agree” to the same question phrased positively (for example, about allowing something). Although the effect in a voting tool context is relatively small.’

So voting tools are never perfect?

‘Exactly. You have to see voting tools for what they are: a tool. Not the absolute truth. Always keep thinking for yourself, look up information, talk to people — and ideally use multiple sources.’

What are the biggest challenges in creating a voting tool?

‘Comprehensibility. Many people don’t understand the meaning of certain terms or the context of a statement. Take something like “The property tax (OZB) should be raised.” People may think: what even is that? Is it currently high or low?

‘When people don’t understand something, they often choose the “neutral” option. But that’s not the same as “I have no idea.” It affects the final result, because neutral answers are counted as matching the positions of centrist parties.

‘Research shows that people don’t fully understand about one in five questions. Sometimes that’s due to an unfamiliar term; sometimes because they don’t know the current situation or fail to see the relevance. If that context isn’t provided directly, most people won’t go looking for it themselves.’

Are there things that could really be improved in voting tools?

‘Definitely. I think there’s room for improvement in offering explanations, like Stemwijzer does nowadays. I’m currently researching whether a chatbot could also help with that.

‘It would also help if political parties were more aware of their language use in the explanations they provide. Parties usually write these themselves, but you often see that they include five new, complicated terms. It’s as if they’re talking to fellow party members, not to voters.’

We’ll soon be heading to the polls again. What’s your advice for voters?

‘Use a voting tool, absolutely. But see it as one of the instruments in your toolbox. Read the newspaper, listen to the news, talk to people. And if you don’t know or understand something: look it up. Don’t be afraid to spend a little time on it. Politics matters. Be consciously engaged with it.’