The psychology behind coalition building: putting yourself in the other person’s shoes as a means to success

Who wants to rule with whom? That is the big question after last month’s elections. Winner D66 faces a difficult task to forge a broad and stable coalition. Anabela Cantiani recently obtained her PhD on this subject and Univers asked her about the psychology behind coalition formation.

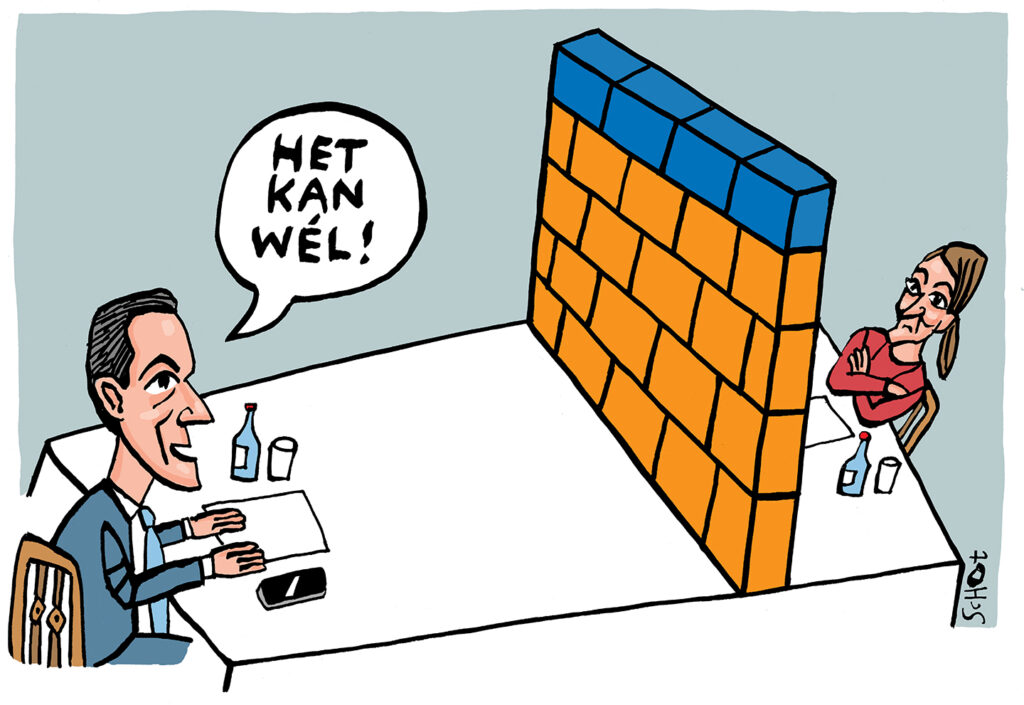

We will not form a cabinet with GroenLinks-PvdA, the VVD stated both before and after the elections. This does not promise to be an easy formation, because a cabinet ‘in the middle’ with CDA, VVD and GroenLinks-PvdA led by D66 has a stable majority in the new House of Representatives. Other variants are more difficult because they require more parties.

To forge a successful coalition, it is useful to put yourself in the shoes of your partners, according to PhD research by Anabela Cantiani at the Faculty of Psychology: ‘In our research, we mainly focused on mechanisms that underlie coalition formation in general, so not just in cabinet formations.’

Signals

Taking perspective is central to Cantiani’s research: ‘We make assumptions about people all the time, and that is normal and necessary to be able to function well socially. To do so, we use signals from the other person to properly assess their motivations. I even do that in this conversation, so it doesn’t just happen in complicated coalition talks in The Hague.’

‘And we use those signals to make assumptions about the other person: does the other person look like me or not, and what does the other party want?’ Cantiani says. Those signals and assumptions also play a major role in politics, even before the coalition talks. Because in political practice it is very important to estimate what are the similarities and differences.

Competition

But what if you don’t want to work together? If you exclude a party in advance, you are not going to put any effort into it, are you? For example, before the elections VVD party leader Dilan Yesilgöz said that she no longer wanted to work with extreme-right-wing Geert Wilders’ PVV, but she also excluded left-wing GroenLinks-PvdA.

That is a bit more nuanced, argues Cantiani, because taking perspective is not only useful in collaboration.

Excluded

‘Even if you are competing with another party, it works well to put yourself in the other party’s shoes,’ says Cantiani, ‘because then you can assess what is at stake for your rival. And it can also be useful if you are at risk of being left out.

‘By concentrating on the similarities, you can estimate on which aspects the other party will make concessions and which aspects are non-negotiable for them. Thus, understanding your counterpart will help you stay in the game. Those who do so are more likely to be included in coalitions.’

Rational

Existing theories about coalition formation are very rational, and do not take into account factors such as sympathy, similarity or other psychological aspects. They focus on power. But Cantiani’s research also focuses on the ‘soft side’ of partnerships. Successful coalition formation depends not only on the level of your stakes, such as the number of seats, but also on psychological understanding, her research shows.

‘Remarkably, in our research we found that when people take the perspective of another person, they often represent the position of the other person in their heads,’ says Cantiani. ‘In their minds, they are almost literally sitting in their chairs or ‘standing in their shoes’.

Cantiani continues: ‘This mental simulation brings people closer together psychologically, a process we call self-other-merging. That sense of closeness seems to be one of the mechanisms by which perspective-taking arouses sympathy and similarity. These feelings can be very helpful in forming coalitions. Relational motives, driven by warmth and understanding, often promote cooperation.’

Stable

But cabinets are not always formed out of ‘love’ for each other. Such coalitions are often a marriage of convenience, born of strategic and business considerations. The Schoof cabinet even ended in an outright divorce. Do such business motives also result in less close coalitions?

‘That depends on the situation,’ Cantiani continues. ‘What is at stake and what incentives can be earned by working together? Ultimately, both motives, relational and strategic, will play a role.

In political practice, too, sympathy and similarity are very important for forging close coalitions. And at the same time, there may be a strategic motive underneath. Because you do feel (emotionally) that it will be easier to govern with someone who looks like you, because you know (cognitively) that you will have fewer conflicts and reach consensus sooner, according to Cantiani.

Shadow

How will the cabinet formation continue? ‘The game that is being played now is not just about the number of seats, Cantiani analyses. Even a small party can exert influence and power if such a party is in a key position. ‘The CDA in particular now has that key position, because they have not yet excluded any parties. As a result, they enjoy more trust than, for example, the VVD.’

So not only the number of seats, but also sympathy and the underlying trust will determine who will do business with whom, Cantiani dares to predict. Initially, the parties go for the safe option, with those they resemble the most. But when you reach the point where the process gets stuck, you will also have to ‘step over your own shadow’, as they use to say in The Hague.