Under Freud’s spell

Mariël Holtermans, clinical psychologist and lecturer in Medical and Clinical Psychology at Tilburg University, has ventured into an enormous task: to read the complete works of Sigmund Freud in two years’ time. As if that isn’t challenging enough, she also keeps a blog about her readings. “It has given renewed meaning to my life.”

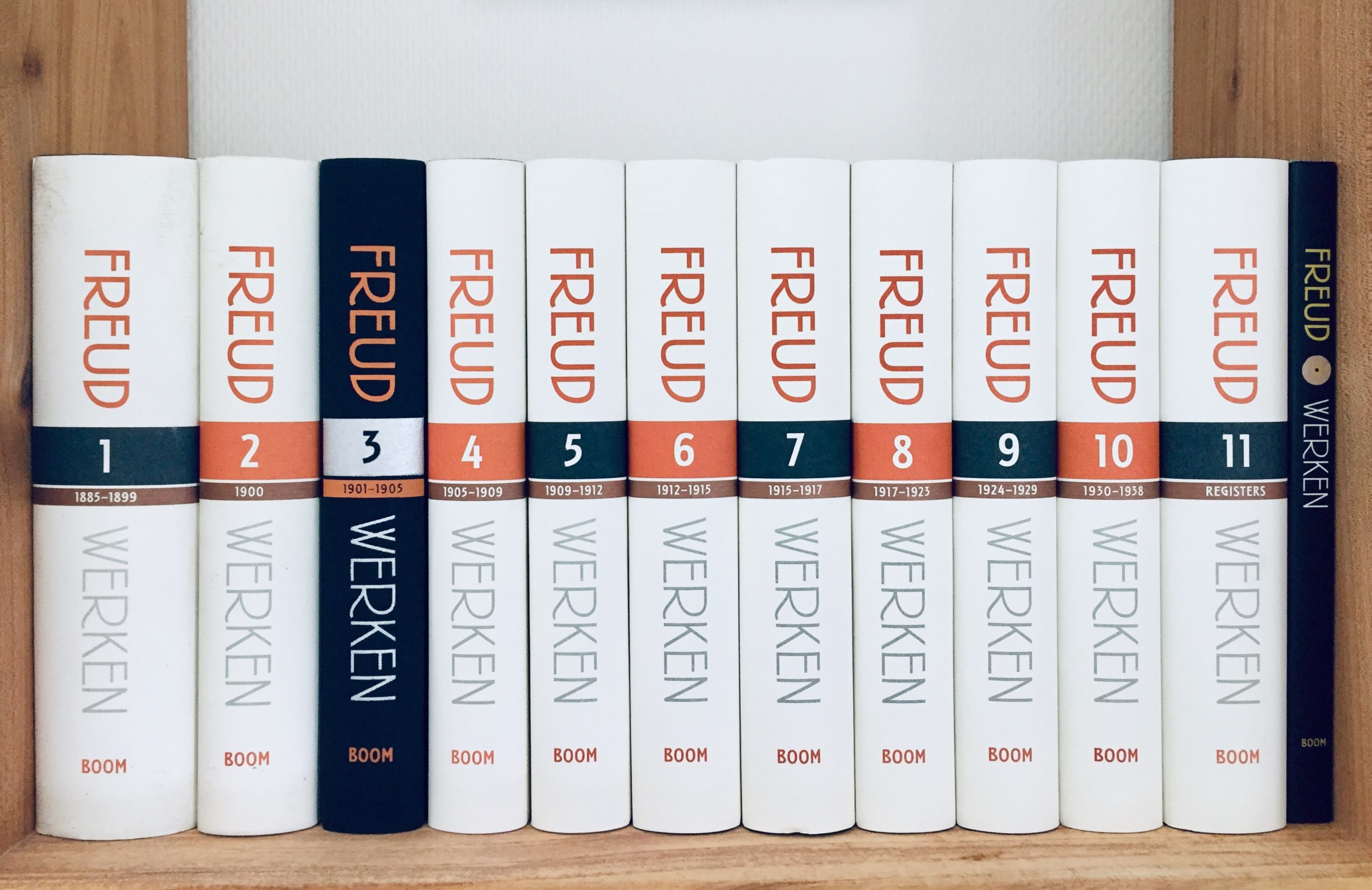

Ten works, six thousand pages in total. Holtermans started in 2018 and has now read almost 2000 pages and written over 100 blogs. A monster task. And the end is still nowhere in sight. Holtermans: “The blog is like a day job. I’m now trying to write two blogs a week. Three if I’m lucky.” Because the project turned out to be more time-consuming than she thought, she gave herself an extra three years to complete it. She now hopes to be done by the end of 2023.

Working your way through 6000 pages of Freud—it seems like a crazy thing to do. What motivates you?

“I have a tremendous passion for studying and acquiring new knowledge—I can hardly get enough of it, especially when it comes to the human psyche.

“The transition from studying to working in a professional environment was difficult for me at first. Although I enjoyed my job, I noticed that I also longed for more theoretical nourishment. I value my work as a therapist greatly, but my passion also lies in reading and writing about more abstract psychological and philosophical topics.

“In order to fulfill this need for depth, I decided to embark on a self-study of Freud. With, in the back of my mind, the hope that one day I might write a PhD thesis on a psychoanalytic subject. That’s secretly a dream of mine.”

Why does psychoanalysis appeal to you? And what is the added value of Freud?

“The added value of Freud and psychoanalysis is in the doctrine of the unconscious. Like Freud, I believe that people are largely driven by unconscious motives. That’s something I experience myself, but I also see it in my clients. I often hear: “I know what is going on, but I can’t change it,” which shows a deeper force within ourselves that our rational mind can’t control.

“Freud distinguishes himself in particular by incorporating these deeper psychological processes into a language. He has come up with many useful terms that describe the underlying dynamics in the subconscious very precisely. By dissecting the human psyche in a meticulous—and at the same time humorous—way, he has given us new insights into mankind.

“And, in my view, he is the founding father of conversation therapy within the field of psychology. This is the classic conversational therapy between psychologist and client. Freud’s therapy consisted of having conversations with his clients, nothing more and nothing less. Even though the patient was simply lying on a couch, it was still a revolutionary way to achieve healing, both mentally and physically, by means of a conversation.”

You write on your blog that partly due to the absence of Freud in the regular canon, you had no choice but to embark on a self-study of his theories. It’s remarkable that someone with such a revolutionary legacy hardly has a place in the textbooks. Is Freud’s work sufficiently recognized in today’s psychology?

“It’s not that Freud is completely ignored within Dutch psychology, but he doesn’t receive enough attention for as far as I’m concerned. However, that is also true for more meaningful figures within the field of psychology. Their original works are more or less crammed into one big summary compilation. As a result, the primary texts only appear in the study program in a distorted form. Only the most important aspects are given a place in the curriculum.

“I think it’s a shame that this is what the study program looks like. That’s my personal opinion, and not necessarily that of the department. By studying the original works, you gain a better understanding of the history of your profession, which also gives you a more complete picture of its current practices.

“To give an example, I refer to current issues surrounding psychosomatic complaints. There are huge waiting lists for people who suffer from such complaints—physical complaints such as pain and fatigue, for which no medical cause can be found. Even before 1900, Freud already wrote about the influence of the psyche on the body. The illness of that time was hysteria. In a case of hysteria, repressed psychological conflicts were believed to cause pain complaints and loss of function of the extremities (conversion).

“Nowadays, hysteria is often dismissed as a silly old-fashioned diagnosis, without realizing that the principles of hysteria and psychosomatic complaints can be of the same nature. In both cases there is often a psychological cause that leads to physical complaints. It’s just the manifestation that has changed. The way hysteria manifested itself at the time is something we don’t see very much nowadays.

“But, in my opinion, studying the original work of Freud can still be very useful to understand the complaints that we encounter in today’s clinical practice. It’s a pity that he has lost significant ground in the Netherlands over the past decades.”

What do you think is the reason for this?

“Freud was accused of being unscientific. His research was mainly focused on case studies: by talking to people for hours, he tried to map out personal processes. His method was qualitative instead of quantitative. This means that he focused on the human experience and tried to understand it (‘verstehen’, as he called it). Something as subjective and impenetrable as the unconscious can hardly be investigated in an objective way. It can’t be located in the brain or converted into numbers.

“Psychoanalytical theory has less and less of a place in the current era, while it’s all the more needed”

“It is this way of doing research that is not compatible with the current understanding of science. I dare to say that 99% of today’s psychological research is based on quantitative standards. In quantitative research, provability is key—to measure is to know. In the end, it must always be possible to translate the result into objectively perceptible results, such as scans and numerical results.

“This shift from a qualitative to a quantitative science may have caused the downfall of Freud. According to many, his claims cannot be substantiated. I would like to see the dominance of the quantitative method change into a more balanced science, in which qualitative analysis is taken more seriously.”

Freud is sometimes described as a ‘poet of the mind’. Poets may describe certain phenomena with great accuracy and marvelous beauty, without it having to be necessarily true; after all, a poem cannot be disproved. Would this label suit him better than that of a scientist, or does it sell him short?

“I think he’s both. From a literary point of view, he’s really excellent. Rarely have I seen someone give such careful and expressive reflections of such a complicated phenomenon as the unconscious and the resulting psychodynamics. Moreover, he often refers back to the past to interpret man’s inner processes with historical myths and legends. His work therefore certainly has a high poetic level.

“However, it would sell Freud short not to call him a scientist. He definitely considered himself to be a scientist. He was trained as a neurologist and tried to substantiate his theories with a scientific basis, such as descriptions of energy pathways in the brain. At the time, however, he was not able to use the brain imaging technologies that are available to us now. Fortunately, there is increasing interest in Freud’s theories on the neurological level—and this has given rise to the new discipline of neuropsychoanalysis.”

Is the status of Freudianism in therapeutic practice comparable to that in science?

“In the clinical practice, Freud’s psychoanalysis isn’t doing so well. The biggest shortcoming of psychoanalysis as a form of treatment is that it takes time to achieve a sustainable result, which makes it anything but cost effective. Ever since market forces entered the healthcare sector, the focus for healthcare providers has shifted to efficiency and quick results. Alternative therapies have outpaced psychoanalysis in this area, pushing it to the side.

“Consequently, the emphasis in the clinical practice has also shifted from quality to quantity. Time and money have become determining factors. Psychopharmaceuticals (medication) are an expression of this mentality and actually represent everything psychoanalysis does not stand for: it presupposes that a disease is caused by a shortage of a certain substance in the brain and that the drug is the quick remedy for it.

“With medication, complaints are indeed reduced in the short term, but one forgets that they are often addictive. The patient also learns little about himself and the cause of his suffering when only medication is used. Of course there are psychiatric illnesses for which medication is absolutely necessary, but that isn’t the case for a large number of psychological complaints.

“We need to move towards a culture where there is more room for self-inquiry”

“Partly because drugs are prescribed so easily, we lose something essential in my opinion: conversation and self-reflection. With the short-term complaint-oriented psychology that is now being practised, there is a lack of a deeper understanding of one’s own nature.

“Ultimately it’s about healing someone’s psychological wounds, and those are hidden in someone’s personal narrative history—you have to work with that. The only way to gain access to this is to engage in conversation. This doesn’t always have to be with a psychoanalyst, it can also be achieved through having conversations with each other.”

How would Freud view the current DSM—the official manual for diagnosing mental disorders?

“I suspect that if he were to rise from his grave and see this, he’d immediately want to climb back in. He would find it too unsophisticated and stigmatizing, I think. The DSM consists mainly of classifications based on observations. So if someone shows behavior X, we call it Y—it’s a checklist of symptoms. No underlying personality dynamics are described that could explain the disorder.

“In reality, each disorder is different and extremely personal. The DSM does not address the question of what a person’s individual history looks like and whether certain events are suppressed in their life. Freud would probably think the current DSM is insufficient.”

A slip of the tongue, it’s happened to all of us. Freud is famous for having renamed this phenomenon as a fruitful source of hidden meanings—unlike others who claim that a slip of the tongue is nothing more than a trivial and meaningless speech error. What exactly is Freud’s idea of this linguistic phenomenon, and do you think there is such a thing as a Freudian slip of the tongue?

“The idea of a Freudian slip is that there is a certain thought lurking in the unconscious, which then surfaces as a slip “with unconscious intent”. The slip of the tongue would therefore give insight into what is occupying someone’s unconscious.

“For Freud, a slip of the tongue is seldom a coincidence”

“I don’t believe—unlike Freud, by the way—that there is a deeper motivation behind every slip of the tongue. There are also slips of the tongue that are caused by the fact that words simply resemble each other phonetically. Still, I think there is certainly some truth to the Freudian slip of the tongue. Like when you mention the wrong name or say the opposite of what you actually want to say. To Freud, pronouncing a totally different word is proof that it must have been in your mind. Freud doesn’t believe in coincidence. Why in God’s name do you say A when you want to say B, that’s odd to say the least.

“A well-known example he cites is that of the chairman who opens the meeting and inadvertently declares the meeting closed. According to Freud, this is a suppressed form of protest that surfaces; he is not in the mood for the meeting. In an inattentive moment, this protest escapes him and is spoken out loud, without conscious intention.”

In addition to criticism of his pseudo-scientific approach, Freud was also condemned by feminists. His works are said to be sexist and anti-feminist. Particularly the passages about ‘penis envy’ raise questions. In addition, he is said to have described women as passive beings. What do you think of this? Does it affect the credibility of his theory for you?

“Although it doesn’t affect the grandeur of his work in my eyes, I do have a problem with his anti-feminist side (but I haven’t read much of it so far, that’s mostly in his later works). At the same time, I also realize that he was a child of his time, and in Vienna of the 1900s there was little room for the emancipation of women. Women were also given a certain passive role in society, which I think contributes to the image he presents.

“In addition, I think men are naturally more aggressive and women more receptive. That can be called passive, but in fact it’s just a social-biological difference that doesn’t necessarily have to be judged. I sometimes wonder how he would react to the feminist wave that arose after his death—excited, indifferent, or maybe even frustrated?”

On your website, you write that you lacked a deeper understanding of yourself and your surroundings. To what extent has reading Freud filled this gap?

“It’s the whole project that I care about. It has given a new purpose and renewed meaning to my life. During my work as a GZ psychologist, I only apply the theory sparingly. At the moment it is mainly a frame of thought with meaningful insights, not practical help. As an academic it does give me the depth I needed. Plus, reading Freud is also therapeutic. You can’t avoid relating his insights to yourself from time to time.”

Interested? Read all blogs from Mariël Holtermans here.