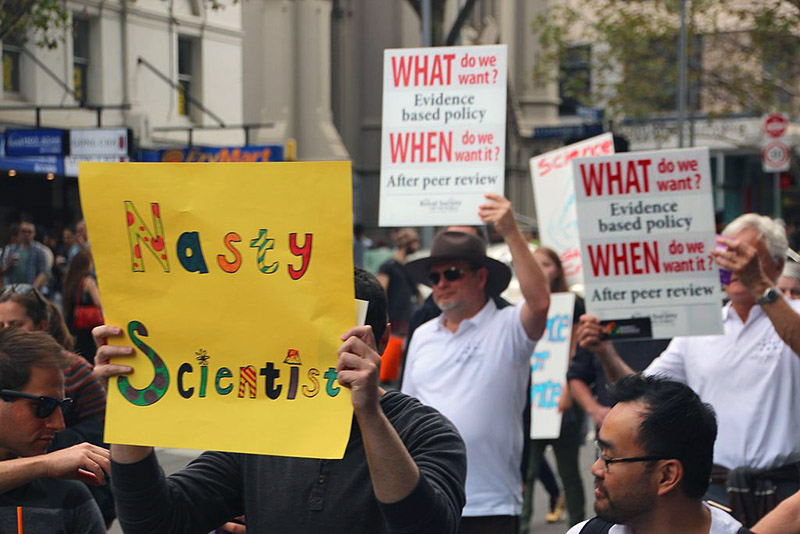

‘Scientists? They are no good’

Science is increasingly under fire. A growing number of people question its authority and societal skepticism about scientific results is rising. And all this while scientists are seeking more connection with society. “People are tired of the scientific method being reserved for scientists.”

There has been a lot of hammering about it in recent years: the scientist must step out of his ivory tower more. He has to get involved in society where the real problems and issues arise. This is called “valorization” in professional terms. It is a win-win situation because as researchers help society move forward, so does people’s trust in science. In this way, scientists do not only serve the citizen but themselves as well. At least, that is the idea.

It remains to be seen to what extent this helping hand guarantees public support for science. The number of movements that are critical of science is growing. Groups such as the protesting farmers and the so-called “climate deniers” are openly wondering why scientists are often followed blindly. At the same time, during the coronavirus crisis, scientific advice is ignored and alternative truths are embraced. It raises questions about the current relationship between science and society. Is there a breach of trust?

Authority crisis

According to Peter Achterberg, Professor of Sociology at Tilburg University, the breach of trust is not that bad. “Science is not having such a hard time as is often claimed. All the research indicates that confidence in science does not decline but fluctuates. Sometimes there is a little more, sometimes a little less. There appears to be no clear, general decline.”

Instead of dark days for science, Achterberg sees heydays. “There is a silent but overwhelming majority that clings to science like never before. Just look at all the people who, during this pandemic, are listening en masse to what the RIVM is telling us.” Achterberg also refers to scientific television programs such as DWDD University (De Wereld Draait Door) and National Geographic, which are very popular among the general public. “Almost everyone loves science.”

Is there no problem at all in Achterberg’s opinion? “Yes, there is. In certain circles, an increasing distrust of science can indeed be observed. It is worth noting that this skepticism is not so much directed against science as a method but against science as an institution. We can speak of an authority crisis.”

With this, Achterberg refers to the following paradox: skeptics believe that scientific research is the best way to acquire true knowledge, while rejecting the scientist as the executor of that research.

The fact that the scientist no longer has the authority he has always had is due to a social unease on the part of the skeptic, according to Achterberg. “People who harbor a distrust of scientific institutions often see the world as complex and disorderly.”

“Science as a method has the potential to interpret and categorize this unpredictable reality,” says Achterberg, “and thereby creates order in the chaos. When people get the feeling that they are not allowed to participate in this method and are excluded by the powerful institutions, it can result in suspicion towards the scientist.”

A revaluation of the scientist

Whether it is right that in today’s society there is more public support for the scientific method than for the scientist as such, is the question. Hans Dooremalen, philosopher of science at Tilburg University, does not think so. He pleads for more recognition of the scientific expert. “Ultimately, it is the scientist who has the best grasp of the scientific method.”

“The scientific method is indeed the most reliable way of gaining knowledge about the world,” says Dooremalen. “What is central to this method is falsifiability. This means that a scientific theory must be refutable at all times. Under the presupposition that a hypothesis can always be incorrect, it must be possible to find the opposite and to falsify the hypothesis.” This is what makes science so unique; it is an intrinsically fallible matter in which ignorance plays an essential role.

A science skeptic is blind to his own failure

Hans Dooremalen

It is of great importance that the person involved in science observes this fallibility. This is done by adopting a critical attitude towards himself and his hypotheses. And that is exactly what the scientist excels in, according to Dooremalen. “A real scientist is constantly looking for objections to his theory. That is why he never claims to possess the truth. This in contrast with a science skeptic, who is blind to his own failure. The big difference is that the scientist questions his knowledge, while the skeptic overestimates his knowledge.”

A scientist’s critical self-reflection prevents him from falling prey to his own bias. Just like any other human being, the scientific expert is susceptible to prejudices, such as the confirmation bias. This is a subconscious psychological process that makes people tend to look for information that confirms already present beliefs. As a result, refuting evidence is either disregarded or ignored.

Dooremalen states that the scientist is less susceptible to such prejudices. “This is evident from his active search for refuting facts. He is aware of the psychological forces that play on him and deliberately tries to counteract them.”

Finally, the added value of the scientist is in his impartiality, says Dooremalen. “A scientist is considered to have no interest in the outcome of his research. In this way, he avoids the risk that his scientific results are used to his own advantage”.

This makes the scientist a guarantee for the objectivity of science. This objectivity cannot be guaranteed when activist citizens —such as protesting farmers—use the scientific method.

Closing the gap

In order to give the scientific institutions and the associated scientists the prestige they deserve, the gap between them and the skeptics must first be closed. Dooremalen sees an important role for science communication here, under the guise unknown makes unloved.

Dooremalen: “The media must be honest and clear about the boundaries of science. They must explain that science is fallible and that it in no way claims to possess the ultimate truth. It is preferable to work with terms such as ‘hypothesis’ and ‘items of evidence’, rather than ‘proven theory’ and ‘proof,’ because these better express the cautious pretensions of science”.

Achterberg doubts whether this transparent approach will have any effect. “The fact that a better understanding of science leads to a better relationship of trust between scientists and skeptics is not something I take for granted. It could even set a counterproductive movement in motion. Skeptics then see how vulnerable and insecure science is, and that it is a human process after all. There is a chance that they will respond by taking matters into their own hands.”

There is a call from society to conduct its own science

Peter Achterberg

“It’s nothing new that skeptics use the gaps of science and offer alternative conclusions,” says Dooremalen. “The problem is that they do this the wrong way. There is almost always a lack of empirical evidence.”

Dooremalen believes that it is especially important to explain what real science looks like. “We must make it clear to people that a hypothesis can only be accepted if it is based on sound empirical evidence. Anecdotes, statements of hearsay or lies are not included in this.” By clarifying this, Dooremalen hopes that people will become more critical of their own methods.

According to Achterberg, it is an idea that is in line with the modern tendency to democratize science. “There is a call from society to conduct its science. People are tired of the scientific method being reserved for scientists and feel the need to check them by means of their own scientific methods and insights.” Achterberg is skeptical about whether this democratization will benefit the position of the scientist. “It is more a consequence of the gap than a potential bridging.”

Translated by Language Center, Riet Bettonviel