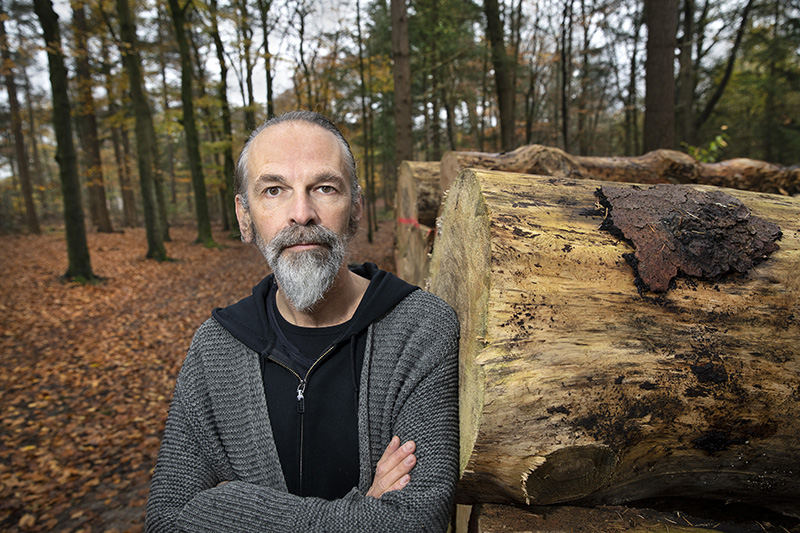

‘The Bible of Feminism’ through the eyes of men. In conversation with philosopher Ruud Welten about The Second Sex

The discrimination of women is a problem of society as a whole, not just of women themselves. Philosopher Ruud Welten read The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir for the first time, and thinks that more men should do so. “After reading it, I felt a sense of shame, but I also felt responsible.”

The Second Sex (1949) by the French philosopher and writer Simone de Beauvoir (1908–1986) is sometimes referred to as “the Bible of Feminism.” In more than eight hundred pages, De Beauvoir demonstrates that women are not born as women, but become women because society sees them that way. Assumptions about what men and women are supposed to be force women into a subordinate, second role.

Today, most men avoid the hefty book because of the touch of feminism attached to it. This was noted by Tilburg University’s associate professor of philosophy Ruud Welten, who took up the challenge. He read The Second Sex from a male perspective. He wrote down his analysis in his latest book Who is afraid of Simone de Beauvoir? (Wie is er bang voor Simone de Beauvoir)

Why does a man want to read the Bible of Feminism?

“Actually, it’s kind of weird that the book is called that. The words ‘feminism’ and ‘emancipation’ hardly appear in it. De Beauvoir initially refused to call herself a feminist, she thought that was old-fashioned. Something from the previous century, the nineteenth, that is.

“As a philosophy lecturer, I am very much involved in existentialism, the movement of thought to which De Beauvoir belonged and to which she contributed a lot. I lecture on the work of Jean-Paul Sartre, one of her partners. I had left The Second Sex unread for too long, at some point I couldn’t escape it.”

The book is a twentieth century classic. I’ve read it, and found it quite hard going. What was your experience reading it?

“I advise new readers to start with the second part, because that’s where it gets really exciting. The first part is long and tiring. That’s because the original French edition was published in two volumes, with more than half a year between the publication dates. By the way, the Dutch translation is not very good, that doesn’t help.

“What I like about the book is the multidisciplinary approach. De Beauvoir writes in a way that was unusual for her time: she approaches women’s lack of freedom from the point of view of biology, literature, history, and psychoanalysis. Nevertheless, The Second Sex is a very uncomfortable book to read, for both men and women. Women who read the book hoping for positive confirmation will be disappointed, and De Beauvoir is also hard on men.

“Her message is that Western society is organized to differentiate between men and women. And that causes a systematic oppression, which makes it difficult for women to move freely through society. By free I mean: free from expectations inspired by myths. This is another reason why The Second Sex is not a feminist book: De Beauvoir does not describe a women’s problem, but a social problem.”

In your book, you make the comparison with a king, who will not support the crowd that is after his head. So why is the socially secondary place of women also a male problem?

“We are talking about a problem of our culture, not a problem for women alone. That’s why we have to do better. Not so much for feminist reasons, but because of our common culture. Because the myths about masculinity and femininity determine the way we think about ourselves. We completely define ourselves in role patterns and do so voluntarily. You can see in our language how unfree our culture is.

“A woman has to think about herself in a language that is masculine through and through, which alienates her from herself. It’s also quite something if you have to constantly talk about yourself in a language that has been forced upon you by a male society. Think of the word ‘master,’ the university degree. We pretend that these are gender-neutral words while they are completely peppered with a gender difference in which the masculine has the highest value.

“The model for a successful person in our society is still that of a man, of the one who is in charge and determines the framework within his own hegemony. De Beauvoir shows that language and culture are masculine, degenerated by centuries of traditions and religious influences. God and his son are both men. That myth, and therefore the way we think about women and how we shape the differences between men and women in language can be changed.”

So the message of De Beauvoir is still topical.

“I think the #MeToo movement has shown that. That wave of shared experiences about abuse of power has shown that there is still a very flat, vulgar male-female difference, in which the man dominates. #MeToo stands for: something has happened to me I have kept quiet about up till now. It showed that these are not incidents, but that our society is organized according to male drives.

“And that while in our time we tend not to talk about male-female differences anymore. We gloss over the differences by saying that problematic relationships between men and women are solved with women’s quotas and diversity workshops. That only makes the problem disappear from sight, but it doesn’t solve it.”

Do your students read The Second Sex as well?

“Today’s students can relate to it more than they did a few years ago. They recognize themselves in what De Beauvoir describes: the problem of a society that is unfree because women are systematically relegated to second place. And, in particular, the systematic form bothers them, the way in which a woman still consciously has to relate to her femininity while a man does not have to do that.

“Look at the term ‘women’s literature.’ When women read other women’s books, they say: I read ‘women’s literature.’ For women who read female philosophers the same applies, they say: ‘I am interested in women’s philosophical works.’ You will never hear a man say: ‘I am interested in male philosophers, or male science.’ When a man speaks, he’s speaking from an erroneous view that he’s using neutral terms.”

What has reading the book brought you?

“A sense of shame and as a result also a certain responsibility. Not only as a man, but also as a lecturer. Our culture is also very masculine in the educational curricula: the philosophy canon consists largely of Great Men. The danger of the myth that history has been shaped by men is dangerous. By repeating that and not doing your best to expand the canon, you get a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“It’s a good start to look at the women who have made important contributions in the sciences and the arts, although you have to look harder for them. We can’t continue as if nothing is wrong, because then the women in the margins will always remain the women in the margins.”

Should all men read The Second Sex?

“Yes, I think it’s a very important book for men engaged in cultural studies, philosophy, and psychology.”

Translated by Language Center, Riet Bettonviel