‘Pure’ misery: how Open Access makes us more dependent on big publishers

It is a public secret that the ambition to make research freely accessible results in a business model. Commercial publishers take over the research infrastructure of universities in order to sell data about researchers to those same researchers. Martijn van der Meer and Juliette Schaafsma sound the alarm.

You have to be living under a rock to miss that a transition to more open science is taking place in the Netherlands. This is evident, for example, from the ambition to make scientific publications publicly accessible. Until recently, the only way to get access to an article was by taking out a university subscription to scientific journals. If you wanted to get over that paywall, you had to pay a few ten-euro notes.

This is an undesirable situation: research financed with public funds was not accessible to the wider public thanks to powerful commercial publishers. State Secretary Sander Dekker (VVD), therefore, decided in 2013 that publicly funded research should be publicly available. By now, Open Access seems like a no-brainer.

At least, you would think so. Because a large proportion of scientific journals are still owned by the exceptionally profitable industry of commercial publishers. Would a company like Elsevier simply sacrifice part of its 982 million dollar annual profit (!) to make science more accessible? Not really, as it turns out.

These publishers have found a new business model in Open Access that not only allows them to make a lot of money but also, via the shortcut of repositories such as Pure, gives them control over the research infrastructure of universities.

The benevolent researchers who—encouraged to do so by their institutions—publish their articles and data on Pure are not only making Elsevier’s coffers richer. They are also giving these enterprises unprecedented power over the university and over their data, with all the consequences this entails.

Open Access via the golden route: the taxpayer still pays double

What is going on? To make research widely accessible, there are several routes. Most ideal is the “diamond” route, where researchers publish in journals that do not charge for publishing and reading articles. However, such journals are scarce and often cannot compete with established high-impact factor journals.

The “golden” route is an alternative. This involves researchers making their articles accessible free of charge by paying a not inconsiderable Article Processing Charge. For example, access to a single publication in the prestigious journal Cell costs 8,500 euros.

‘The taxpayer pays not only for the research, but also for the publication of that research’

To be able to deal with these kinds of amounts, universities conclude so-called “read and publish” deals with large publishers. In these deals, an amount is agreed for which articles become publicly available without the need to pay Article Processing Charges or take out institutional subscriptions.

Publishers would not be publishers, however, if they had not stipulated a maximum on the number of articles that can be published “free” in Open Access. If this quota is reached before the end of the year—as is now the case with Springer Nature —then universities have to use their own funds. So, the taxpayer pays not only for the research itself but also for the publication of that research.

The “green” route as a way out or as a prelude to more commerce?

One way out seems to offer the so-called “green” route to Open Access. In 2015, the House of Representatives passed a motion (Dutch only) by Joost Taverne allowing researchers to remove articles created with public funds from behind the paywall and make them publicly available after a “reasonable period of time.” The VSNU stipulated that six months after publication is reasonable and that publication must take place via an institutional repository.

Institutions decide for themselves what kind of repository they use. Some universities use a database that they host and manage themselves; others outsource this to an external party. Tilburg University, for example, uses Pure for archiving publications. That seems an understandable choice.

Pure provides insight into what is published, where, when, and by whom. And if you are not committed to the “Recognition and Rewards” programme, via the Fingerprint and Research output functionalities, it is also possible to create a profile of the productivity of individual researchers.

Until you realize that Pure is owned by Elsevier. In 2012, the company acquired Danish startup ATIRA, which had been marketing Pure for several years, and whose created software was welcomed with open arms by universities worldwide.

The trap of Pure

And so, a rather tragicomic picture emerges. Because whether researchers opt for the “golden” Open Access route recommended by the university or the “green” Open Access route, Elsevier stands to gain. Even if researchers were to make all their articles available via the green route in Pure, the multibillion-dollar company would still earn handsomely. What is more: this makes universities even more dependent on Elsevier.

And that is exactly what is intended. After all, Elsevier is not stupid. The possibilities of the Internet, but certainly also the worldwide enthusiasm for Open Access, make it clear that in the future there will be less and less money to be made from publishing scientific articles.

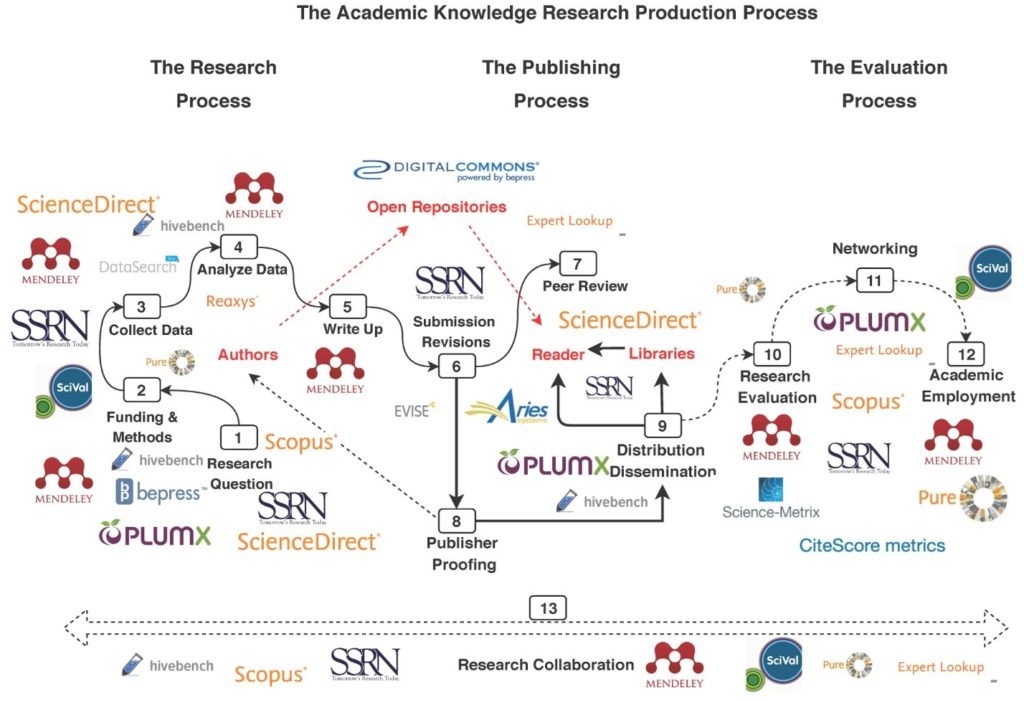

And that’s why Elsevier is increasingly acquiring companies that take care of parts of the research cycle. Many researchers will be familiar with Mendeley, ScienceDirect, Scopus, and SSRN Submissions/Revisions. All are owned by Elsevier (see also the figure).

Just think how much data from and about researchers is processed through all these systems and what a commercial company can do with it. Elsevier themselves say they want to contribute to evidence-led human resource decisions by using their SciVal business intelligence software. In the future, managers would then be dependent on the information that Elsevier manages to decide, for example, who gets a permanent contract or who can or cannot be promoted.

And then there is the genuine risk that universities will become so dependent on commercial parties such as Elsevier that they will be able to use a ‘vendor lock-in strategy’ to drive up the prices of services such as Pure in an uncontrolled manner.

This is exactly what happened in the second half of the twentieth century with institutional subscription fees. Then, too, universities and researchers allowed mission-driven journals to be bought out from under their noses or pulverized by profit-driven alternatives.

Alternative scenarios

Fortunately, alternative scenarios are possible. The basic assumption being that scientists themselves remain in control of their science and that publicly funded universities are value-driven, democratic institutions, not publication factories serving the interests of commercial parties.

1) To start with, it is out of date to create quantitative profiles and communicate them externally as a marketing instrument via the Fingerprint and Research output functionalities based on data retrieved via Pure. To break free from the tentacles of a publisher such as Elsevier, researchers could choose to remove their data from Pure themselves and do the administration of research output themselves.

It would be even better if the Fingerprint and Research Output options in Pure were turned off at the institutional level. Most other Dutch universities have long done so. A good alternative to an external research profile is to use an ORCID ID. This is linked to a “persistent identifier,” which in turn can be linked to all the research output of a researcher. The beauty of ORCID is that the researcher remains in control, and it is funded by the institutions, which are not profit-driven.

‘It’s time to formulate a vision for a sustainable, independent university’

2) Regarding publishing, it is absolutely preferable to ensure good, mission-driven Open Access platforms funded by knowledge institutions or the scientific community itself. In Tilburg, for example, we can be very proud of our own Open Access publishing company for books. Here the publication and use of all material is free because the university chooses to make this financially possible without interference from commercial parties.

There are also similar Open Access journals. It depends on the field whether it is possible to publish in these kinds of “diamond” Open Access journals, but it is a salutary path.

3) If researchers still want to publish in journals of commercial publishers, then a way should be found to archive articles that fall under the Taverne amendment in a place over which the university itself has full control, for example, by hosting the database on campus and managed by our own staff. This would eliminate the need to use the database function connected to Pure.

4) A more radical step could be taken by researchers themselves. With the Taverne amendment in hand, they could, in theory, publish publications that had previously appeared behind a paywall in a publicly accessible archive such as HAL, Zenodo, or Humanities Commons.

This is not without risk, as there is no case law on the Taverne Amendment and there is a chance that commercial publishers will sue. However, one might ask whether the potential consequences of a scientific community under the control of commercial publishers do not justify taking such a risk.

Administrative courage

It could be that Tilburg University’s administrators explicitly decided that we should be dependent on commercial parties for almost every part of the research process. We find this hard to imagine: this scenario is not in line with a university that claims it primarily wants to grow “in impact.”

We understand that the user-friendly portals of commercial parties seem attractive and that the development of alternatives costs time and money. However, we also fear that the outsourcing of vital research processes to external, profit-driven parties stems from a lack of vision of a sustainable, independent university. It is time that we formulated this vision and started to act accordingly. While we still can.

Juliette Schaafsma is a full professor at the Department of Communication and Cognition. Martijn van der Meer is research policy officer at the Tilburg School of Humanities and Digital Sciences.