Street harassment: a problem of society

Calling, hissing, being chased: many women feel unsafe on the street. Street harassment is common but does not always get the attention it deserves. Univers talked about it with assistant professor of social psychology Ivana Vranjes and assistant professor of clinical psychology Gaëtan Mertens.

What is street harassment?

According to CBS, in 2020, two out of every three women and girls were harassed on the street. But it remains difficult to give a precise definition of street harassment. Most scientific studies describe it as “unwanted sexual attention from strangers in public spaces.” In addition to verbal harassment—”Hi sweety,” “Do you want to fuck me?” and “Gay!”—it can also involve nonverbal behaviors. These include stalking, making gestures and sounds, unwanted public display of genitals, and overt masturbation.

There are also scholars who go a step further and also refer to acts such as physical violence, sexual assault, and rape as street harassment. A fixed definition of street harassment is also difficult because an intimidating experience is personal and context dependent. As a result, people may experience a similar situation differently. One woman may find it offensive when someone shouts at her, while another woman is less bothered by this.

But just because something is not perceived as harassing does not mean that sexual violence or harassment is not occurring, says Ivana Vranjes, assistant professor in the Department of Social Psychology at Tilburg University: “Because little attention is paid to street harassment, many women have subconsciously taught themselves to minimize the problem and deal with it passively. Yet, it can have an impact on how women feel and behave in public spaces.”

Many forms of street harassment can also be ambiguous and, as a result, may not seem inappropriate at first. A form of “pretend friendliness,” Vranjes explains: “When someone addresses you on the street and asks where you are going, it seems very innocent at first. But there are unspoken norms. One of those norms is that you don’t ‘just’ ask strangers on the street where they are going. This is because you are entering someone’s personal space. This question can seem innocent at first glance, but at second glance, it can create a feeling of unsafety.”

Social problem

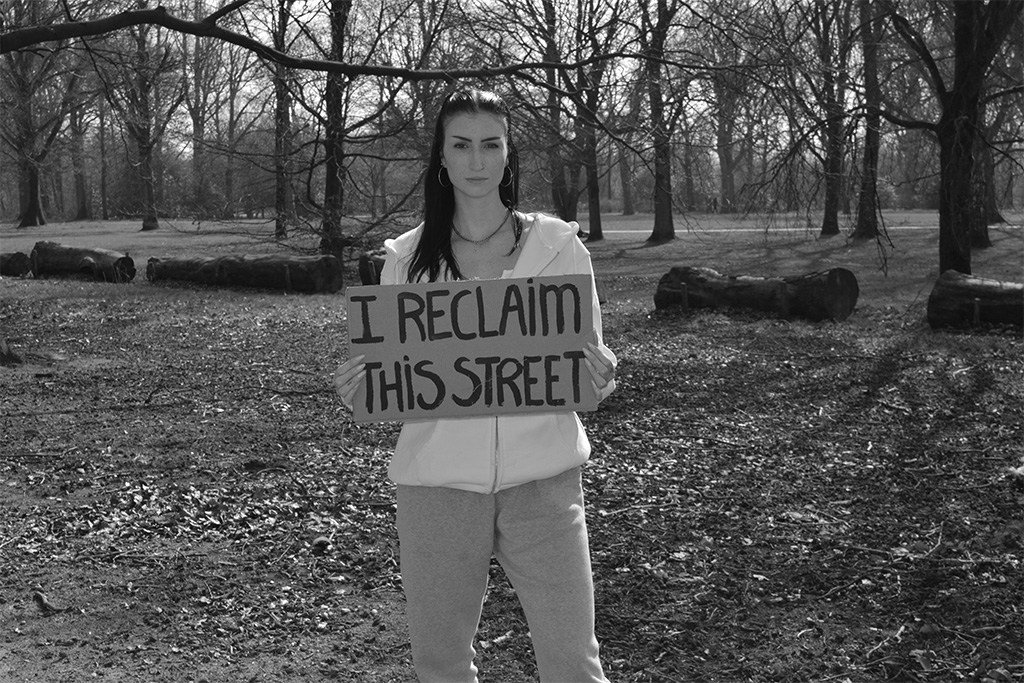

According to sociologists, problems such as street harassment are only “social problems” when a large portion of the population speaks out against them. The attention for street harassment has increased significantly in recent years. Also in Tilburg, there are more and more initiatives that focus on the presence and prevention of street harassment. For example, Tilburg Municipality has opened a street harassment information line. There are also citizens’ initiatives such as Reclaim NL by Tilburg’s Noëlle Zarges, in which she calls on women to “reclaim” the streets.

But despite the growing attention, street harassment remains an understudy in the debate about transgressive behavior. Concerns about sexual harassment in the workplace and domestic violence overshadow the issue. A disturbing observation says Vranjes: “Street harassment is in danger of falling off the priority list because it is seen as something innocent. People often don’t understand the harmful effects it can have on a victim and that—along with domestic violence and sexual harassment—it is part of a larger social problem.”

In fact, academic research in 2015 from Hastings College indicates that street harassment is part of a dominant culture that values male power and the oppression of women and other groups seen as inferior. Assault on women and children, subordination of women in politics and society, homophobia, inequality of opportunity, racial profiling, and the wage gap are just a few examples of social problems that are also part of this culture. All of these problems are closely related and, as a result, silently blend into one another.

Consequences for victims

The negative consequences for victims of street harassment have also been scientifically documented. Research shows that victims suffer from psychological and emotional consequences such as anxiety, distrust, depression, stress, sleep problems, shame, physical insecurities, and the fear of going into public spaces.

Therefore, street harassment is more than just an annoyance. It causes women to be less present at certain places and times in public spaces because they are aware that there is a risk of a possible confrontation. Experiences of sexually transgressive behavior, violence, or having witnessed it, fuel this rational fear.

Gaëtan Mertens, assistant professor in the Department of Clinical Psychology at Tilburg University, explains that this avoidant behavior is part of a learning process: “When you are harassed on the street, you learn to avoid certain places at certain times. This is because you learn that there is a chance of being harassed in these environments.”

Victims vary in assertiveness in their responses—”fighting”—or passively—”fleeing”—to harassing behavior. The Hastings College study states that most women respond passively to street harassment. Ignoring the assailant, pretending that the harassment is not offensive or not happening, walking in a different direction or actually walking faster, smiling, and feigning disinterest are all examples of passive responses. Other women actually use assertive strategies. They confront the assailant and explain to him, for example, why his behavior is unpleasant. In addition, they often use non-verbal gestures—such as “the middle finger”—and are more likely to contact the police or other authorities.

“If you know how to react in a certain way in a certain situation, you have a sense of control over it. But if you don’t know how to react, or you tend to freeze, this can increase the feeling of threat. Isolating yourself and avoiding possible danger zones such as the pub, public transport, or the street can be a consequence of this,” explains Mertens.

Solution

The #metoo revelations have caused a huge increase in the attention paid to sexual harassment. Yet these revelations also lead to division. According to Vranjes, this division stands in the way of a solution: “#metoo also evokes resistance. Many men feel attacked by these reports. This is because they are being addressed in a negative way about their gender identity—their ‘manhood’—and resist the idea that men are by definition the perpetrators.”

As a result, these men are trying to revalue themselves, so they feel better about their gender identity. A problematic development, says Vranjes, “We need to look for a new way to approach this problem without creating a battle between men and women. Instead of polarization, collective feeling must be stimulated. In this way, a society is created in which we all win.”

Men must, therefore, be part of the fight against gender inequality. “Fortunately, there are enough men who are already willing to work on this. What is important is that they are made aware of the problem of gender inequality in a ‘not too offensive way’ and what they themselves can do to ensure a better and safer environment,” Vranjes states.

In addition, Vranjes argues that it is important to teach children early on to respect each other’s wishes and boundaries: “If children behave inappropriately because they use indecent language or show violent behavior, for example, intervention must be prompt. By doing so, they learn to recognize and safeguard other people’s boundaries. The men who harass women on the street today continue to do so because no one addresses them about their behavior. Perpetrators therefore get the feeling that this is possible and allowed. The more (and earlier) we teach people to recognize certain behaviors as unacceptable, the more likely it is that bystanders will intervene.”

The scientific results cited in this article are from: ‘Street Harassment: Current and Promising Avenues for Researchers and Activist’ written in 2015 by Dr. Laura S. Logan & ‘From ‘Ghettoization’ to a Field of Its Own: A Comprehensive Review of Street Harassment Research’ written in 2021 by Bianca Fileborn and Tully O’Neill.

Translated by Language Center, Riet Bettonviel