Refugees: then and now

In the section Telling History, we take a dive into Tilburg University’s rich Heritage Collections. This time Irma van Bommel and Emy Thorissen talk about Brabant photographers who portrayed refugees.

Migration is of all times. Around the world, people are fleeing war, poverty, persecution, or oppression. Photographers have been reporting on streams of refugees for decades, trying to get their photos published in the hope that action will be taken, and an end will be put to the degrading conditions in which refugees find themselves. The recent stagnant reception at COA (Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers) in Ter Apel is a downright disaster. After Heumensoord in 2015/2016, now also a refugee camp in Ter Apel?

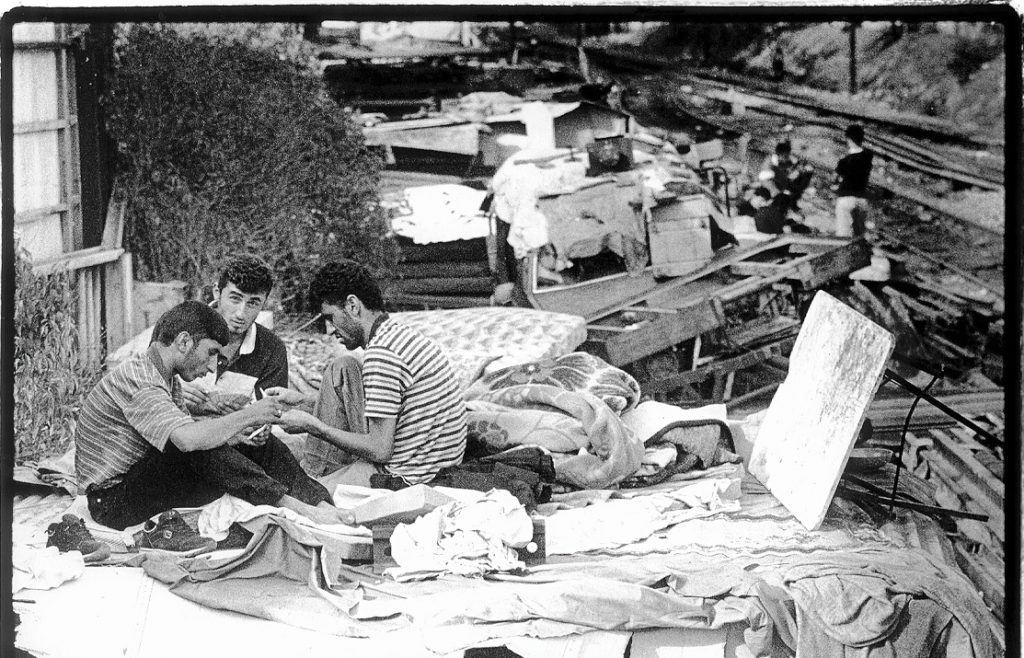

During the early 1950s, photographer Martien Coppens (1908-1986) traveled to West Germany and Austria several times, where people fleeing the communist regime lived in old bunkers and hutted camps. With journalist Fred Thomas and Father Wiro van Aken (head of the Dutch East Priest Aid Department (Oostpriesterhulp)), among others, Coppens visited the Charlotten bunker in Frankfurt-Höchst.

His photos appeared in the Catholic magazine Echo van de Liefde. Money was raised through the Catholic community to help Christian fellow believers who had fled. To that end, Coppens also wanted to publish a book of photographs, Ontheemden, but it did not get beyond a dummy.

It was the years of reconstruction, just after World War II, and there was a housing shortage all over Europe. That made it difficult for Eastern European refugees to find a place in society. Even now, at least in the Netherlands, there are too few homes, which is one of the reasons why the reception of refugees is problematic.

Fortress Europe

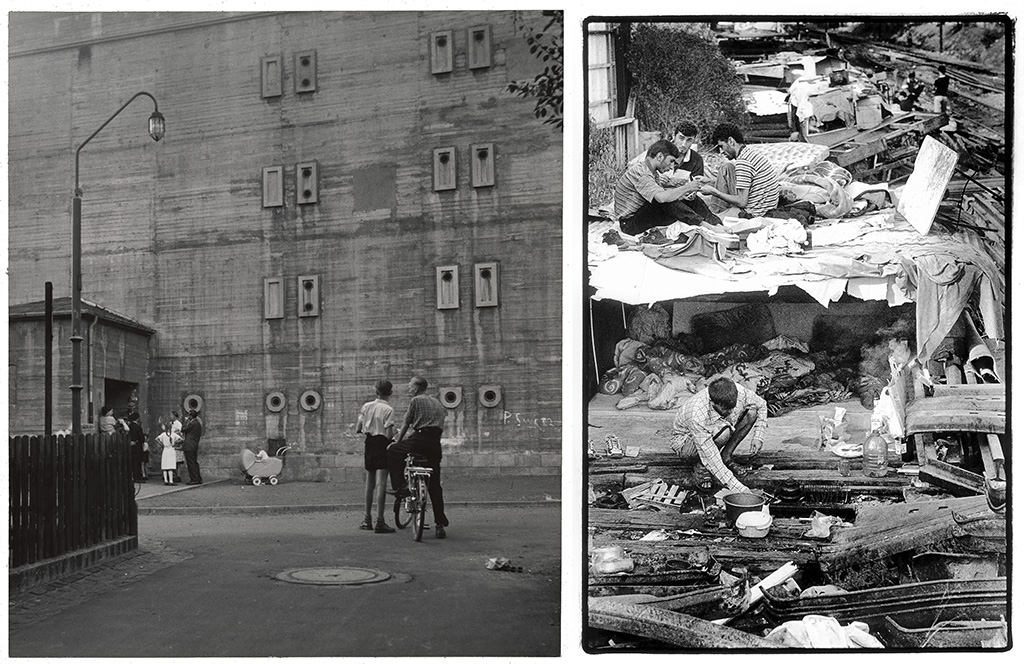

In 1989, the Iron Curtain fell and the first refugees from Eastern Europe were welcome in free and prosperous Western Europe. That changed during the 1990s, refugees were stopped at the Oder-Neisse border between Germany and Poland. From then on Piet den Blanken (1951-2022) photographed refugees trying to enter Europe. But the influx became larger and larger, and in order to keep out “economic” refugees, Europe became more and more of a fortress. With harrowing situations as a result.

‘We live on an island of prosperity in a sea of misery’

“No distinction should be made between people fleeing violence and those migrating for poverty and hunger,” Den Blanken said at a discussion session on migration during his exhibit at the Pennings Foundation in Eindhoven last year. “We live on an island of prosperity in a sea of misery. They are not the exception; we are the exception.” The exhibition showed an overview of twenty-five years of migration, mostly of people who tried in vain to reach Europe but were stopped by border guards or died by drowning at sea.

Text continues below photo.

Visual historiography

The newspaper was Den Blankenship’s stage. “Yet, I want my photographs to last longer than tomorrow’s newspaper. I hope my work will become a kind of visual historiography.” His wish, then, was for his photo archive to be housed at Tilburg University’s Brabant Collection.

He died unexpectedly of pneumonia in April this year while on a coverage of Nicaragua and Guatemala. Had he had the chance, he would undoubtedly have photographed the dire situation in Ter Apel as well as the Ukrainians who are welcome and the other refugees for whom Europe’s borders remain closed.

What a disaster!

October is History Month. This year’s theme is “What a disaster! It prompted this contribution, previously published in the journal In Brabant, year. 13, no. 3 (September 2022), pp. 46-55.

Brabant photography is one of the focal points of the Brabant Collection (housed in the Tilburg University Library). Martien Coppens’s vintage prints and archive are managed here. Soon, the entire oeuvre of press photographer Piet den Blanken will also be transferred to the Brabant Collection.

About the authors:

Irma van Bommel is an art historian and associate at the Pennings Foundation in Eindhoven and writes for the online journal Brabant Cultureel.

Emy Thorissen is also an art historian and works at the Brabant Collection at Tilburg University Library as curator of Old and Special Collections and is picture editor and editor of In Brabant.

Translated by Language Center, Riet Bettonviel