AI makes me distrust my own writing

Students are recording themselves to prove they’re not using artificial intelligence. ‘We’re obsessed with how we use AI,’ writes Yeşim Topuz. ‘Writing is starting to feel less like thinking, and more like covering yourself.’

I delete an em dash. Then I put it back. Then I delete it again. Suddenly, I wonder what it says about me. Somewhere along the way, certain punctuation marks have started to feel like ‘evidence’ of using AI, making me question my writing habits. Yet, here I am, hovering over an em dash – does it look too deliberate, too polished or like something I didn’t write myself? It isn’t just about writing style, it’s about a system that has stopped valuing the human process of thinking and started valuing only the polished result.

AI is everywhere, but rarely spoken about. In the Netherlands alone, nearly a quarter of the Dutch population uses AI programs such as ChatGPT, with higher usage among younger adults. Normal as this has become, it sits uneasily with how academic work is evaluated and trusted. That raises a broader question: how do we deal with something that isn’t going away anytime soon, and what does that mean for learning, education and credibility?

It already affects the way students write. Some feel like they need to ‘dumb things down’, choosing simpler words or leaving sentences less smooth than they could be. Others use software that tracks every keystroke as they’re writing. And yes, some even record themselves writing. Writing starts to feel less like thinking on the page, and more like covering yourself.

Institutions, too, are trying to catch up. While some of my courses use the university’s AI Index to determine to which extent AI usage is appropriate, they also use detectors like Turnitin. But these tools are reported to be unreliable and not meant to be the sole basis for academic–misconduct decisions. Vanderbilt University’s Centre for Teaching published a report in 2023 showing that Turnitin’s AI detection flags real writing from real students at an inflated rate. Students of Color as well as students whose first language simply isn’t English are disproportionately affected. How?

AI is not free from bias. The data used to train them often reflects a Western, English-centric norm. Consequently, they unfairly flag diverse writing styles as machine-generated and bias adds up through several stages; data imbalance, non-native speaker penalty, stereotyping bias and false positives or negatives.

The shift from ‘No AI’ to ‘Transparent AI’ is a start, but it misses the deeper rot. We are obsessed with how we use AI because we are refusing to ask why we feel we need it. If we are terrified that an em dash makes us look like a machine, perhaps it’s because academia has been asking scholars to write like machines for years.

Even before ChatGPT, scholars were already under pressure to publish constantly, producing more than anyone could realistically read. For reference: More than 5 million articles are published yearly, with exponential growth rates around 5.6% per year! How do we even meaningfully engage with that amount of articles?

Knowledge is treated as output, scholars as producers, and research as a commodity tailored for monetization. In that sense, AI does not disrupt the system, it fits it perfectly. When value is tied to productivity rather than thought, writing becomes a means of survival, not reflection. The real question, then, is not why people use AI, but why academia demands this pace at all.

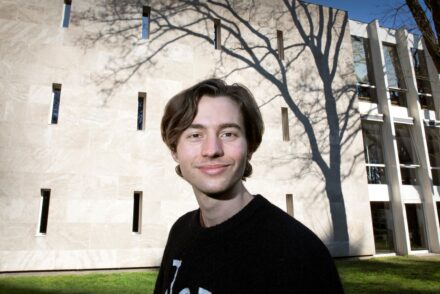

Yeşim Topuz is a bachelor’s student in International Sociology at Tilburg University.