Atlas of European Values: from progressive boomer to conservative youngster

How do Europeans think about abortion, sexual orientation, solidarity, and migration? The recently published Atlas of European Values: Change and Continuity in Turbulent Times answers these questions and more. Univers spoke about the importance of this large-scale European study with Tim Reeskens, national program director of the European Values Study in the Netherlands and Inge Sieben, within the EVS team responsible for valorization and impact.

European or Dutch? Tilburg associate professors of sociology, Inge Sieben and Tim Reeskens, do not have to think long about that question: there is no need to choose. “Many of our respondents indicated that they are both; you can have multiple identities,” says Sieben. “In any case, I feel myself to be Dutch and European.” Reeskens wholeheartedly agrees. Although, for now, Belgian and European for the time being: “I’m in the process of naturalization.”

What binds Europe, a number of researchers from Tilburg and Leuven asked themselves in the late 1970s. Or rather: “the Christian values, are they still there?”, Sieben specifies. It was the beginning of research that has been going on for more than forty years now: the European Values Study (EVS). Quite soon the approach was extended to include questions about family, work, migration, and democracy. The first data collection took place in 1981, in the member states of the then European Community (EC), the predecessor of the current EU. It turned out to yield a wealth of information and insights, and it was decided to repeat the study at regular intervals.

An extensive job

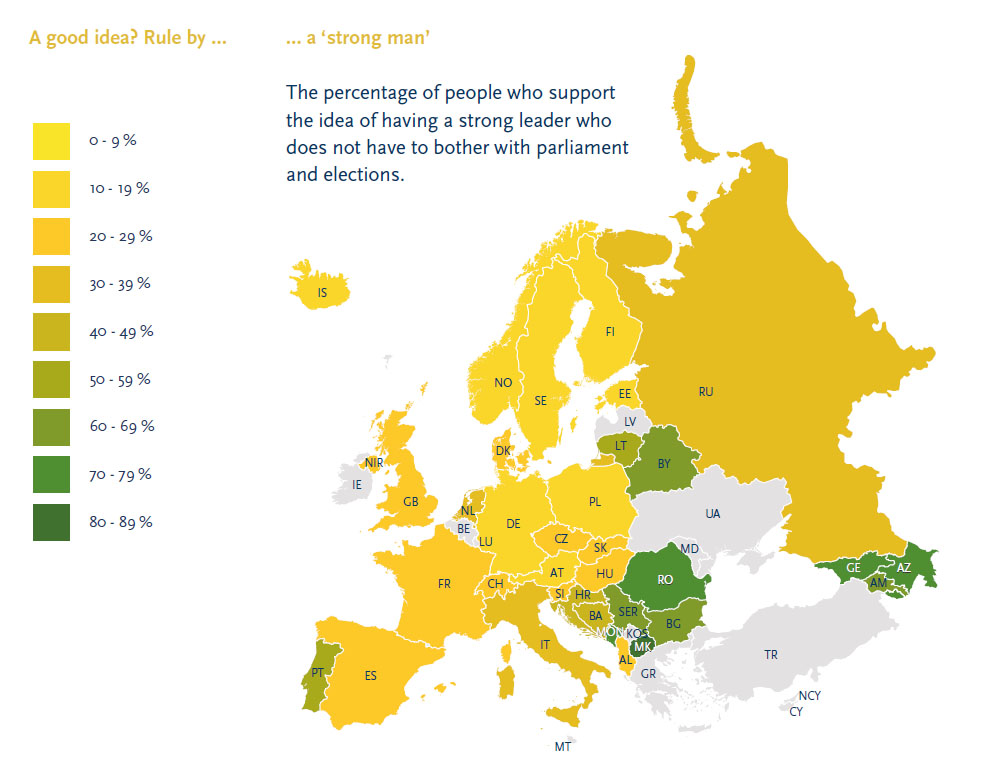

And so, every nine years, research teams visit 1,500 randomly selected fellow nationals in almost all European countries, EU and non-EU. From Iceland to Portugal and from Russia to Great Britain. With questions about how they would like to live next door to someone who is gay, whether they would like a strong leader in their country who is not bound by elections and how satisfied they are with their lives with (or without) children. The results end up in the Atlas of European Values. The latest edition of which was recently released in open press for the first time.

Every time, it is a large and complicated job, Sieben explains: “The research teams from the various countries are responsible for data collection and financing. We work with interviewers who visit the people at home and that comes at a pretty high price tag. The fact that we manage to do this in so many countries time and time again is actually quite remarkable.”

People often give the same answers throughout their lives to questions about how they view abortion and euthanasia

Sometimes it does not work out Reeskens adds: ” On the maps in the atlas, you see some grey colored countries, including Belgium and Ireland, these have not been successful in getting the funding. And so, we have no data from those countries. Very unfortunate.”

Stable values

According to the sociologists, the importance of all this data is not primarily in interpreting current issues such as: what does the European think about the increased flow of refugees from Ukraine? Or: to what extent do people place trust in the current political leaders? “There are other kinds of polls and surveys for that,” Reeskens said. “For us, it’s really about getting a good view of social change, whether the values of a society change systematically over time. So, we work with a large time span, the last data collection was in 2017 and the next one is not until 2026.”

Previous research shows that people are generally quite stable in their values and beliefs. Most people give virtually the same answers throughout their lives to questions about which political system they prefer or about moral issues, such as how they view abortion and euthanasia. The greatest change in values occurs between generations, according to the researchers.

“A generation is a group of people who grew up in a similar way, at the same time, with specific economic, political, and cultural circumstances,” Sieben explains. “The values you have are closely related to when and how you grew up, in what context. In the European Value Study, we follow the generations through time. For example, we see what answers the group that grew up in the 1960s gives in 1981, 1990, 1999, 2008 and in 2017. Moreover, in each subsequent data collection, new generations are added.”

More conservative youth

After decades of following generations, what is most striking? Societies and especially the youngest generations are not becoming more progressive. It is a development that social scientists also call cultural “backlash.” Reeskens: “The most recent data collections from 2008 and 2017 show that the youngest generations, born in 1990 and 1999, embrace slightly less progressive and slightly more authoritarian values.” People in their twenties and thirties (in Dutch) generally judge abortion, divorce, euthanasia, and suicide less positively than, for example, the baby boomer generation. They also prefer non-democratic forms of government such as experts who make decisions for the country or a strong leader who does not have to worry about parliament and elections.

Surprising, according to Tilburg sociologists. For a long time, many social scientists assumed that the progressiveness of new generations is growing, due to an increase in wealth and education and reduced religiosity. Also called the modernization theory.

Future research will have to show whether the youngest generations remain more conservative

Scientists do not yet have an unequivocal explanation for the return to a more conservative mindset. Uncertainty about the future seems to play a role in any case. Reeskens: “The idea that actually every job is threatened by technology such as self-learning systems and that everything is more efficient because of technology leads to uncertainty; will I still have a job, what does it look like? Or think about the tension in the housing market; will I still be able to get a house? That economic uncertainty potentially translates into more conservative values.”

According to Inge Sieben, the cultural aspect is also important. “The more progressive baby boomers grew up in a time when the church was still very much in charge, and they were able to resist that and thus create their identity for themselves. But young people now; where can they get their identities from? They are searching, who am I and what do I belong to?

Future research, according to both sociologists, will have to show whether these youngest generations indeed remain more traditional and conservative in their values, and whether this will be true for the generations after them.

Less solidarity

Another striking trend the researchers discern: Dutch people seem to be showing less and less solidarity with each other. Reeskens: “When it comes to concern for the unemployed or sick, for example, and for humanity in general, it appears that the Dutch have deteriorated somewhat. You see that, on average, we think that you can think your own things and be who you are, but apparently that also goes hand in hand with less concern for each other.”

Some fellow sociologists, according to Reeskens, wonder if the Dutch have become more individualistic. “That you have to choose your own life path more and more, but as a result you can count less on others? That’s something to think about and keep an eye on in the coming years.”

Making sensitive issues negotiable

The mountain of EVS data is not only interesting for researchers but also gives policy makers and politicians insight into the values of their citizens. “We presented the Atlas of European Values in Brussels in early May, and it was well received there. Because this atlas is completely open access, we can distribute it easily. In the near future, it will also go to all kinds of politicians in Europe,” says Sieben.

Teachers find it challenging to discuss acceptance of homosexuality with their pupils

The researchers see another important purpose in education. Sieben: “I am coordinator of the international project, European Values in Education, EVALUE, where we make teaching materials with the maps and graphs from the atlas. Among other things, pupils can make interactive maps that show how Europeans think about a wide range of topics. They can also compare values among countries, time, and different groups in society.”

It can be a great way to bring sensitive topics up for discussion in a class full of adolescents, Siebers continues saying. “Teachers find it quite challenging to discuss subjects such as the acceptance of homosexuality or of certain migrant groups with their pupils. By having young people fill out the same questions as our respondents, they learn to think about their own viewpoints and to talk about it with classmates.”

Want to take a look for yourself? You can find the Atlas of European Values here.