Who is the scientist?

Can you become a scientist if you love gaming, or if your parents didn’t go to university? Of course you can, writes Kevin van Schie. And it’s important that children know that too. ‘If, as a child, you see that some scientists look like you, the academic world suddenly seems a lot less distant.’

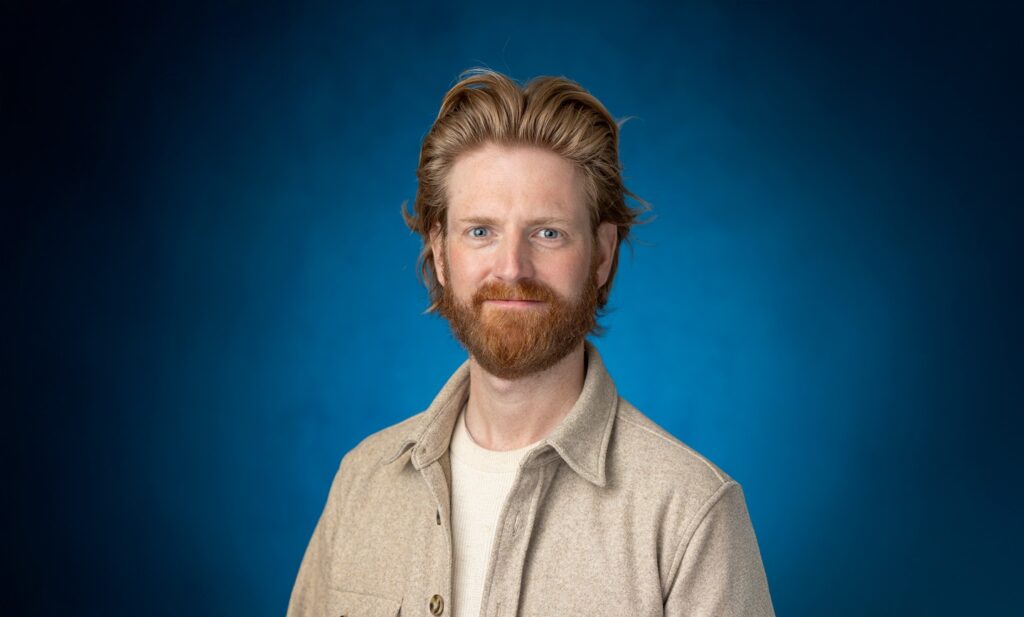

‘Is this a scientist?’ a mother asks her nine-year-old daughter, pointing at a life-sized banner of a man. The man on the banner is wearing a dark blue jacket and sneakers, smiling kindly, and apparently enjoys working on his old car in his spare time. Her daughter looks unconvinced: ‘No, he’s probably a handyman.’ They continue looking. ‘What about this woman with the glasses?’, ‘Yeah, she looks smart. She must be a scientist!’

Welcome to Night University Junior, where children enter the world of science in their own curious and energetic way. At Tilburg Young Academy, we played our detective game with the children. Five banners featuring real employees from Tilburg University (scientists and non-scientists) are placed around the room. The children don’t know it yet, but in this game, they’re actually scientists too. They get to ask smart questions to find the answer to the central question: which of these people is a scientist?

The responses are endearing, sometimes funny, but above all, revealing. Apparently, the young visitors of Night University Junior already have a fairly fixed idea of what a scientist looks like or does. And that idea is often only partially accurate. The image of a scientist (in both children and adults) is usually based on stereotypes: an older white man, preferably with glasses or a lab coat. You might already be picturing him: Einstein with his wild hair and tongue sticking out. The icon of the ‘real’ scientist, right?

This is a rotating column from the Tilburg Young Academy (TYA). Each month, a different TYA member highlights developments in the academic world.

During the game, children discover that scientists don’t all look the same, and that many didn’t excel in primary school. They learn that scientists study very different things (often without a white lab coat!) and that none of them planned to become a scientist when they were kids. As the game continues, we talk more with the children. What actually is a scientist? Can a scientist enjoy sports, or are they mostly bookworms? Does it matter if your parents went to university if you want to become a scientist yourself?

In just 30 minutes, we try to challenge assumptions in a playful way and start a conversation about stereotypes, hoping to shift some misconceptions, even if only slightly. If a child believes that science is only for people with highly educated parents, a certain appearance, and specific hobbies, that can (often unconsciously) become a barrier to engaging with science. Yet science benefits from diversity and fresh perspectives.

If, as a child, you see that some scientists are like you – that they love gaming or dogs too – then that (academic) world suddenly feels a lot less out of reach. Because university doesn’t begin with enrollment in a bachelor’s program, and not even in high school. It begins in primary school, the moment a child realizes that science is also about their questions: what are clouds made of? Who decides what’s fair?

That’s why we should make science and the university more accessible by showing that scientists and non-scientists come from diverse backgrounds. That they are people with hobbies, doubts, dreams, and yes: sometimes glasses. And maybe, just maybe, a child will think: I want to be a scientist too.

Would you like to play the ‘Who is the Scientist’ game with children? Get in touch with the Tilburg Young Academy at youngacademy@tilburguniversity.edu.

Kevin van Schie is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Medical and Clinical Psychology. He conducts research on memory, emotion regulation, and climate anxiety.